A night in the life of an astronomer at Australia’s largest optical telescope

The road that leads up to Siding Spring Observatory from the small town of Coonabarabran in New South Wales provides a postcard-perfect view.

A chain of mountain peaks and rocky outcrops of the Warrumbungle National Park surround the bushland as the road snakes its way up the mountain. Three wedge-tailed eagles circle in the cloudless blue sky above the jagged peaks.

This is the view that greets astronomers as they come to this ANU-run observatory to make ground-breaking discoveries about the cosmos.

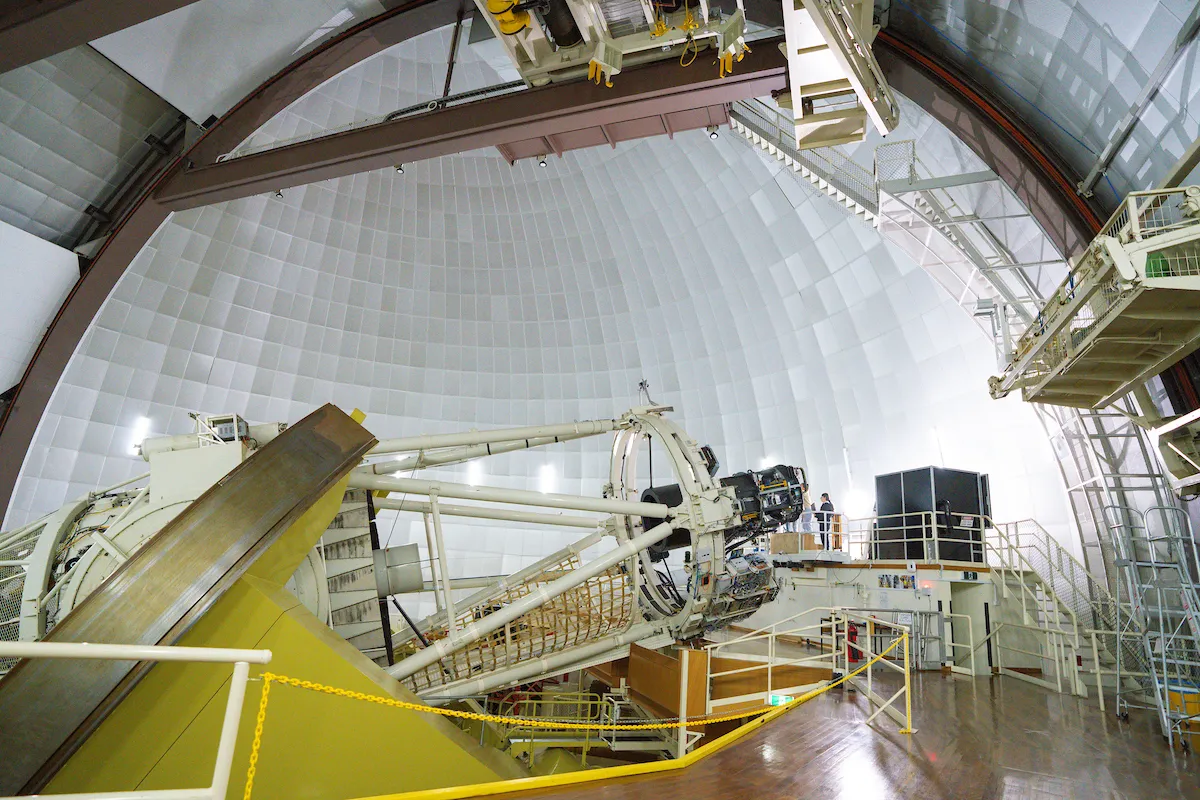

Even from kilometres away, it’s easy to spot the largest of the telescopes: a big white column with domed top, sitting on the highest peak like it’s some kind of inland lighthouse. It is known as the Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT). The AAT is one of a number of telescopes of varying sizes, housed in mostly white domes dotted around the landscape of Siding Spring Observatory.

During the day, tourists and school groups mill about the Visitors Centre here, but behind the boom gates the place is quiet (apart from a few technicians unobtrusively going about their work maintaining the telescopes). The action here happens at night.

Come with us as we find out what a night in the life of an ANU astronomer at Siding Spring Observatory is really like.

2.30pm

Dr Stefania Barsanti from ANU Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics along with PhD candidates Gabriella Quattropani from Macquarie University and Susie Tuntipong from The University of Sydney wake up in their rooms at the Siding Spring Lodge. Thanks to the black-out blinds they can sleep well through the morning.

They head to the communal kitchen and help themselves to brekkie. The researchers chatter, eat their cereal and drink coffee as they prepare for a night of observations with the AAT.

3pm

Stefania, Gabriella and Susie walk into the AAT building, which is home to Australia’s largest optical telescope (the mirror is 3.9 metres wide).

The project they’re working on is called the Hector Survey. It’s a massive six-year project involving multiple institutions across the globe, and the Hector team members take turns to be on the ground collecting data.

“Hector is the instrument that's currently mounted on the telescope. It's an integral field Spectroscopic Survey instrument for galaxies,” Stefania explains.

This means that Hector produces spectrographs of light wavelengths, where they can analyse the make-up of gases within each galaxy. From that data, astronomers can tell a lot about the properties of more galaxies than ever before.

The researchers get out of the lift on the sixth floor at the control room, where they’ll spend most of their night. As you enter, there’s a little kitchenette on the left, then a few couches and a coffee table for breaks (featuring Tim Tams awaiting the inevitable midnight munchies).

It is partitioned from the business end of the room, which is full of computer monitors for the researchers to run their codes, calibrations and to gather and view data – and a panel that controls the movements of the telescope itself.

Also importantly, Gabriella checks a screen showing the weather radar. They need a clear night to gather proper data. Thankfully, tonight looks perfectly free of rain or clouds.

3.10pm

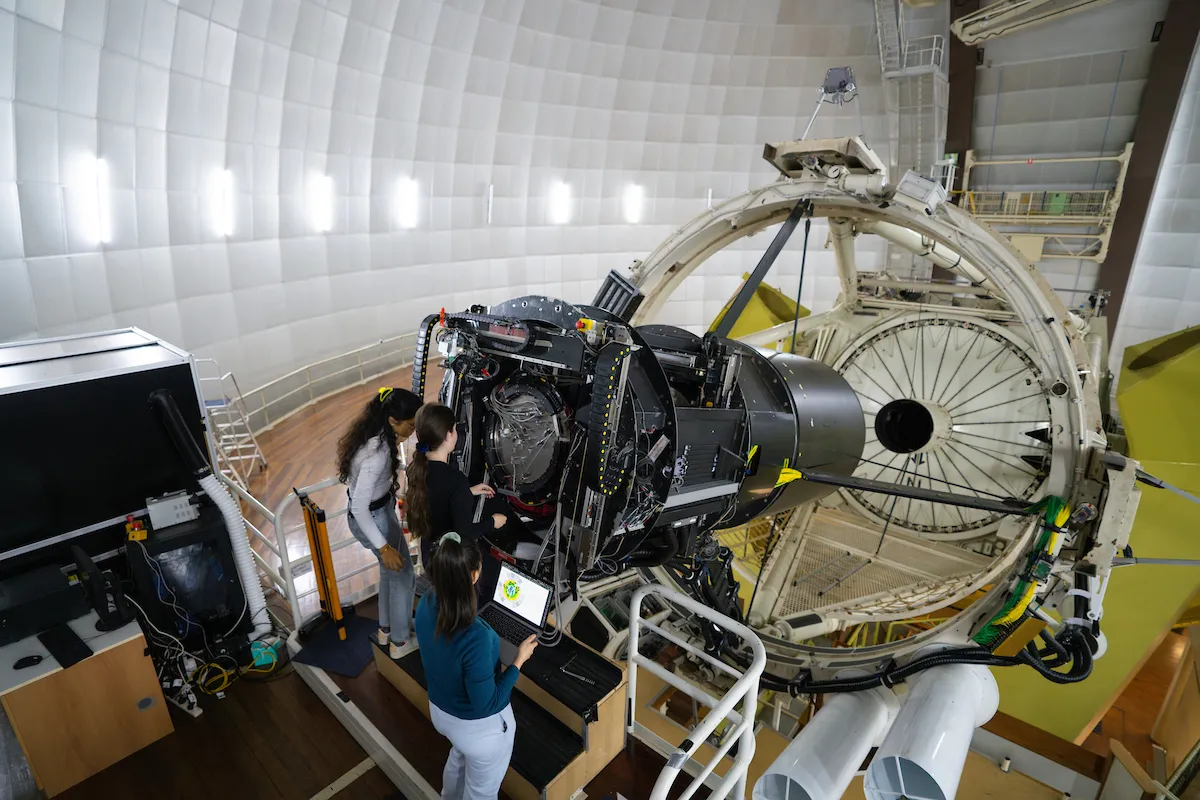

Through a corridor and up some steps, the three researchers reach the Top End, where the actual structure of the telescope looms large under the domed ceiling.

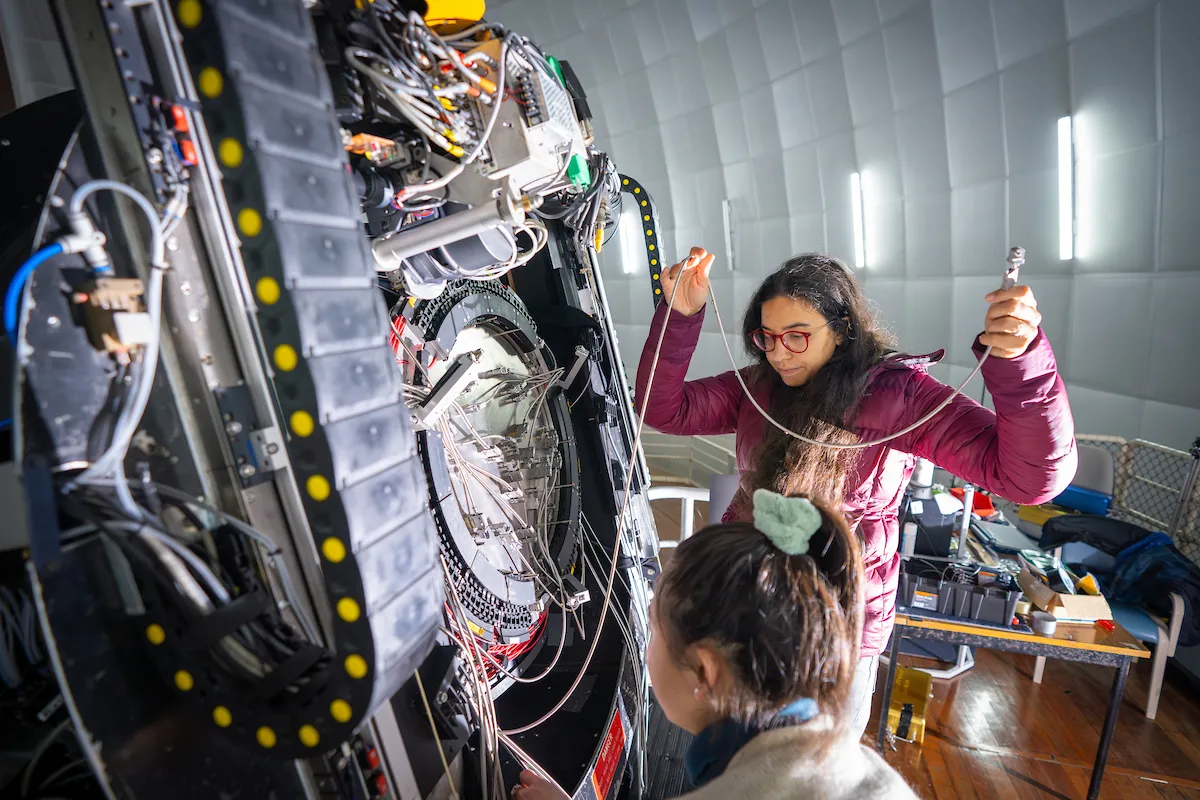

The major job now is to “change the plate” on the end of the instrument. This involves carefully unclipping a bunch of specifically arranged magnets and bundles of fibre optic cables, removing and replacing the metal plate from the end of the instrument, and then re-attaching the cables in the new configuration − all according to a special key.

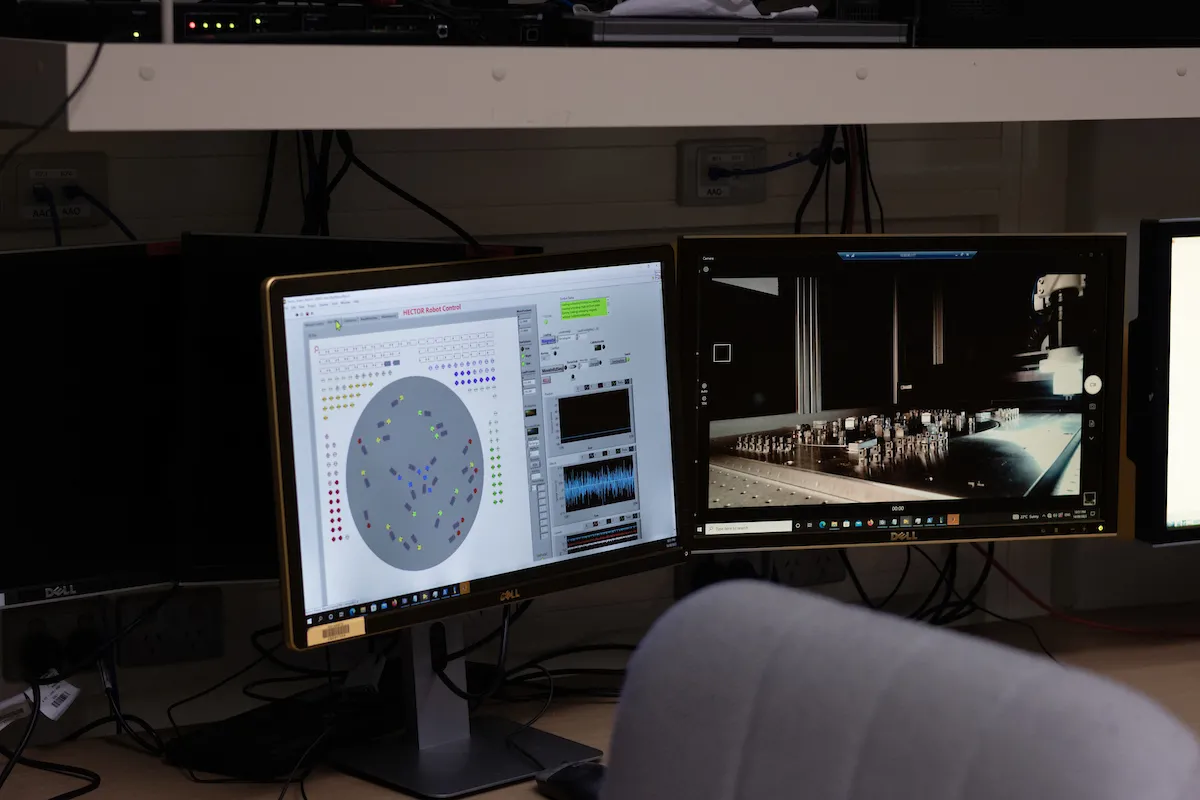

The plates are configured by a robot that is way more precise than a human could be to direct the telescope at the exact spots in the night sky that they are targeting that night.

The quicker they work, the sooner the team can start gathering data. The clock is ticking.

4pm

Back in the control room, the researchers start running codes on the computers to calibrate the daily light and temperature.

“This can take two minutes, or two hours,” Stefania says.

But once the codes are all running, there’s a little moment to break.

They slip outside and watch the sunset over the observatory and Warrumbungle National Park from the catwalk – the narrow balcony that circles the building on the sixth floor. Up here, you are at the same height as the little swallows zipping through the air. Below are the little domes of the other telescopes, the kangaroos grazing and hazy bushland seems to stretch out endlessly. It is a magical place to be at sunset.

But as the light fades, the work is just beginning for the astronomers.

5.55pm

At the official time of twilight, the team need to calibrate the telescope. You can hear and feel a low rumbling vibrate through the control room, as the night assistant directs the telescope to the right angle and signals the shutter to slide open.

Slowly, as the shutter panel open it reveals the twilight sky, allowing Hector to capture the data it needs.

6.20pm

Now the sun has set, and the flurry of the set-up tasks is over, ‘lunch’ is calling. Tonight the cook has prepared a beef and veggie stew with rice and garlic bread. The meals are put into the fridge and personally labelled – when the astronomers have time they pop down to the Lodge kitchen and collect their food.

When moving around the observatory you have to be careful not to create too much light, which disturbs the astronomical observations. You can walk and adjust your eyes to the dark, or take a very low light torch with you. You can hear students and researchers chatting and their feet crunching over the gravel.

To drive to another telescope you must keep your lights on ‘parkers’, and take it very slowly, being mindful of wildlife.

Thanks to these efforts to reduce light pollution in the region, the stars appear to shine brighter than ever out here.

7.30pm

Stefania, Gabriella and Susie are back in the control room. While the monitors flash up with the spectrographs that they need, the researchers monitor their many screens to make sure all is going to plan.

For each new plate on the instrument, they aim to observe seven times for half an hour.

“Tonight, we're going to have information for around 40 galaxies for the whole night,” says Stefania. “That’s just 40 out of the 15,000 galaxies that will be sampled for the Hector Galaxy Survey.”

Once the full survey has been completed, scientists like Stefania will be able to answer all sorts of questions about the evolution and nature of galaxies.

9.30pm

A small glow appears on the telescope cam. It’s a grass fire somewhere in New South Wales, the night assistant says. He’s not too concerned, but is keeping an eye on the fire reports.

Stefania sets the Hector robot up to move the magnets as needed on the spare plate remotely from the control room.

“We have a webcam camera that's looking at what the robot is doing. So we can see it's going to go and pick up magnets and put it in the plate,” she says.

11.00pm

It’s time to change the plate of the instrument again at the Top End. This process works the same as before, and the researchers return to action and concentration mode, moving the fibre optic cables around as they need to – this time kept cosy with extra beanies and coats as the temperature in the dome has cooled down considerably.

“This is a special place because many astronomers don't actually have that opportunity to do this more hands-on job,” Stefania says.

“Almost everything is remote nowadays in terms of observing, so I feel really lucky to be able to come here and get to play with the instrument.”

1am

It’s past midnight and time for some ‘night lunch’. The researchers grab snacks from the kitchenette fridge to fuel them through the rest of the run.

The night assistant notes that the fire that had been in the distance earlier has fizzled out (thank goodness).

Now the researchers continue their next sets of observations until dawn breaks.

5.40am

As twilight rolls around and the sun begins to peek over the Warrumbungles, the team wrap up their work.

Stefania, Gabriella and Susie grab their coats and bags, jump in the lift and head back down, walking out into golden light of the daybreak, tired after a big night of astronomy.

It’s time to bunker down, close the blinds and get some sleep, before they do it all over again this afternoon.

You can see for yourself what it’s like behind the scenes at Siding Spring Observatory, Coonabarabran NSW, when it opens to the public once every year for Starfest. Starfest is 29-30 September 2023.