Could you survive a trip to Mars?

At a 2019 public lecture, Dr Emma Tucker posed a question to the audience: who would like to travel to space? Almost everyone raised their hand. But would they still be so keen once they knew the possible health risks?

I often wonder what it would be like to travel to Mars. When I do, I think about the logistics involved.

How long will it take? Will I fly past the moon? Can I expect a bumpy landing? And more importantly: How will I get home?

Most of the technology needed to address these questions has already been invented, or is at least on our near horizon. We have landed several spacecraft on the surface of Mars, and NASA’s Curiosity rover is currently sending back regular updates that are changing what we previously knew about the Martian planet.

With enough time and money, it’s safe to say that science has got this.

But overcoming logistical challenges are only part of the solution. When considering any trip to space, we should also be asking ourselves questions like:

What does space travel do to the human body? Can I cope with being isolated from my friends and family for that long? And: What happens if I have a medical emergency in space?

So you need to talk to an astrophysicist who is also a medical doctor

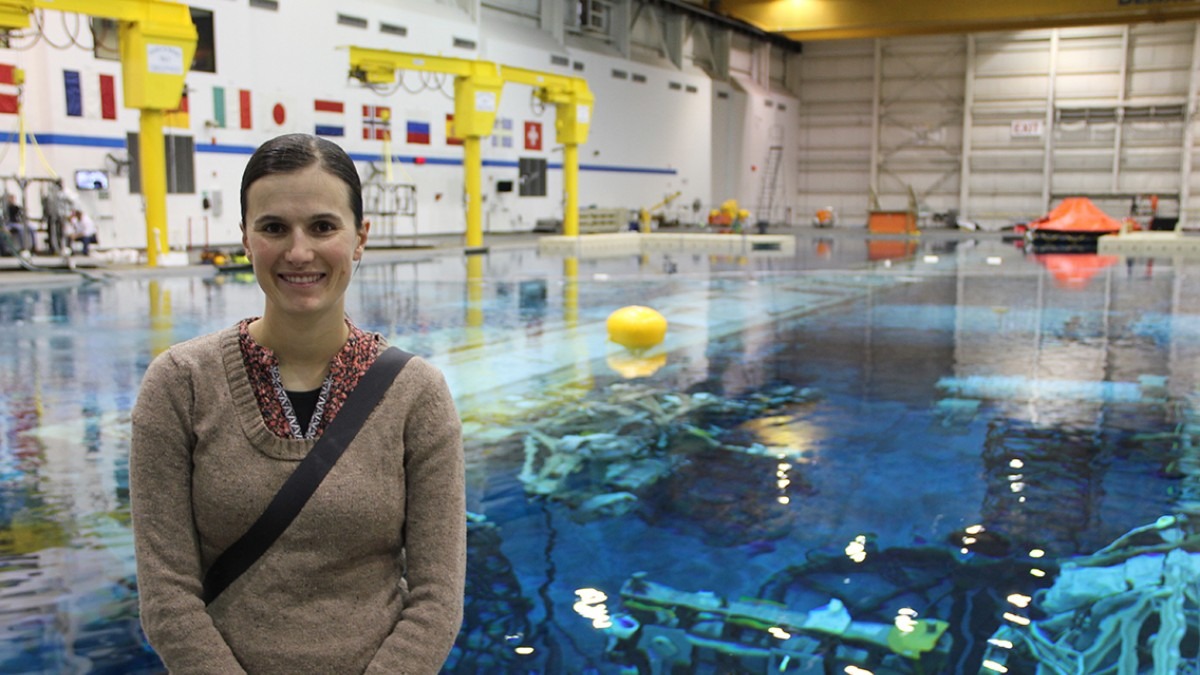

I can’t think of anyone more qualified to run you through a pre spaceflight medical checklist than Dr Emma Tucker from Calvary Health Care in Canberra. Not only is she a double doctor – with both a PhD in astrophysics and a medical degree – she has also completed an aerospace medicine clerkship at NASA.

“A trip to Mars is outside anything that has been experienced by humans,” explained Dr Tucker, when she visited The Australian National University recently to deliver the first of a series of Dean’s Lectures on Medical Moonshots.

A major obstacle to surviving a trip to Mars and back, is living without Earth’s gravity.

“There is essentially no knowledge of what exposure to microgravity for that long may do,” said Dr Tucker.

Mars does have some gravity; more than the moon, but less than Earth. But for the trip there and back you will be in a microgravity environment, floating weightless for up to seven months.

Dr Tucker explained that even for shorter periods, exposure to microgravity results in muscle and bone density loss, visual impairments, and potential heart and lung problems. For those who have not experienced microgravity before, the first likely medical implication is vomiting.

Very soon, it won’t just be astronauts experiencing this.

You too can travel to space – for the right price

Civilian tourists will be able to travel to space as early as this year, thanks to companies like Virgin Galactic. This changes things significantly.

“One of the biggest problems is what happens when you put the average person into space,” said Dr Tucker.

I was among the minority of audience members at the lecture who said they weren’t ready to leave Earth. I just don’t think I’m the ideal candidate.

But one day soon, travelling to space will be more like boarding a flight, where the company you fly with doesn’t even care about your medical history.

“Very soon, the average space traveller is going to be an elderly person,” said Dr Tucker.

“They have had an entire lifetime to accumulate the wealth to go on a flight. They have got to a stage where potentially they are more prepared to take the risks associated with space flight.”

And having elderly people up in space will definitely increase the likelihood of something going wrong.

How do you dial 000 from space?

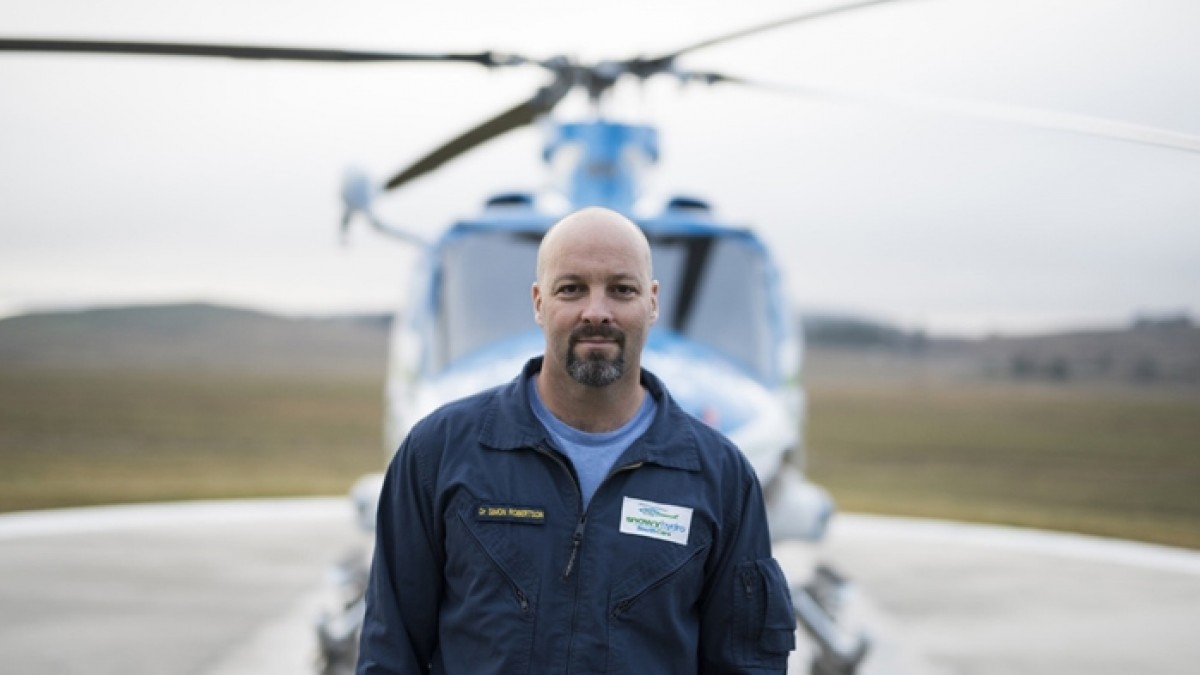

If a medical emergency does occur on your spaceflight, having someone on board like Dr Simon Robertson would be ideal.

Dr Robertson is a Senior Lecturer in critical care and emergency medicine at the ANU Medical School. Along with psychologist Professor Kate Reynolds, he was part of the panel discussion following Dr Tucker’s lecture.

As a medical doctor on the crew of the Snowy Hydro SouthCare rescue and retrieval helicopter, he knows a thing or two about addressing medical emergencies in unusual environments. But admits that emergency care in space is a big unknown.

“I couldn’t think of anything more foreign than being in a microgravity environment,” said Dr Robertson.

In Dr Robinson’s line of work, it pays to help a patient as much as you can before you get into a confined space. “The idea broadly, is to get all dressed up before you put anybody in an aircraft.”

If a patient is very short on oxygen, Dr Robinson explained, they need to consider partial pressures of oxygen at altitude. “We sometimes ask our pilots to run the coast at lower altitude instead of taking us over the hills for example.”

And this is on Earth. It is becoming clear to me that medical care in space is even more complicated than I realised.

Even if I could afford it, and I definitely can’t, I don’t think I will be booking a trip on Virgin Galactic.

What about mental health? R U OK in space?

“The longest anyone has ever been in space is cosmonauts on the Mir space station” said Dr Tucker. “That was around 430 days, and that is less than half of what a likely Mars mission could be.”

We may not know what the long term exposure to microgravity may do, but it is possible to have a guess at what the psychological implications may be.

As an expert in social and organisation psychology, Professor Reynolds from the ANU Research School of Psychology understands the issues likely to arise.

“There are examples where there have been reports of mental health deteriorating in space,” said Professor Reynolds.

“Imagine hanging out with people you work with for six months, day and night. Six months living, eating, sleeping with your work colleagues. It is going to take some special training to be able to manage those environments.”

As Professor Reynolds explained, the combination of isolation and confined living and working quarters can severely impact your mental health. The longer the mission, the more these issues emerge.

“It is also high consequence. You need everyone to be top of their game.”

Along with effects of microgravity and mental health issues, there is another health risk on Mars that I haven’t mentioned yet. And it’s not Martians.

Radiation exposure is one of the biggest dangers

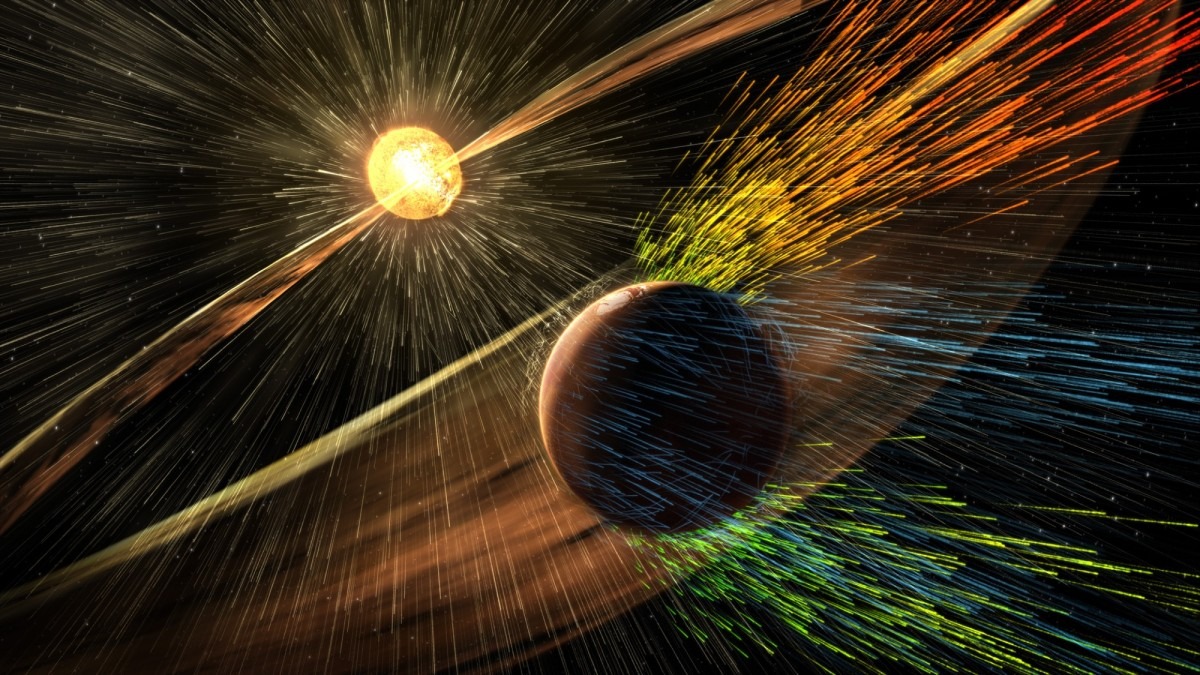

Aside from providing gravity, an atmosphere and fresh water, the Earth does provide another condition beneficial for our survival: an extensive magnetic field.

This field – called a magnetosphere – shields us from the worst of the Sun’s radiation. It stops solar winds from eroding away our atmosphere, and is responsible for the auroras visible over the Earth’s poles.

“Long duration spaceflight around the Earth to a certain extent is okay, because you have the protection of the magnetic shield around Earth. As soon as you go outside that, it is a problem,” said Dr Tucker.

Mars does not have not have an equivalent magnetosphere, resulting in much more harmful radiation reaching the Martian surface compared to Earth.

This increases the risks of Mars explorers developing cancers, cataracts and degenerative cardiac disease. “Currently there is no known way to create enough shielding to an astronaut potentially going to Mars,” said Dr Tucker.

Dr Robertson thinks that finding a solution to long term radiation exposure will be the most important problem to overcome when travelling to Mars.

“It is going to involve accepting a small amount of risk, knowing that despite large doses of ionizing radiation, not everybody gets sick with it,” explained Dr Robertson.

He said that since we use radiation to treat so many different cancers in so many different ways, a solution may involve mitigating the effect of radiation on the body. “Rather than trying to shield the body in the first place.”

So the mission to Mars may help our health here on Earth too

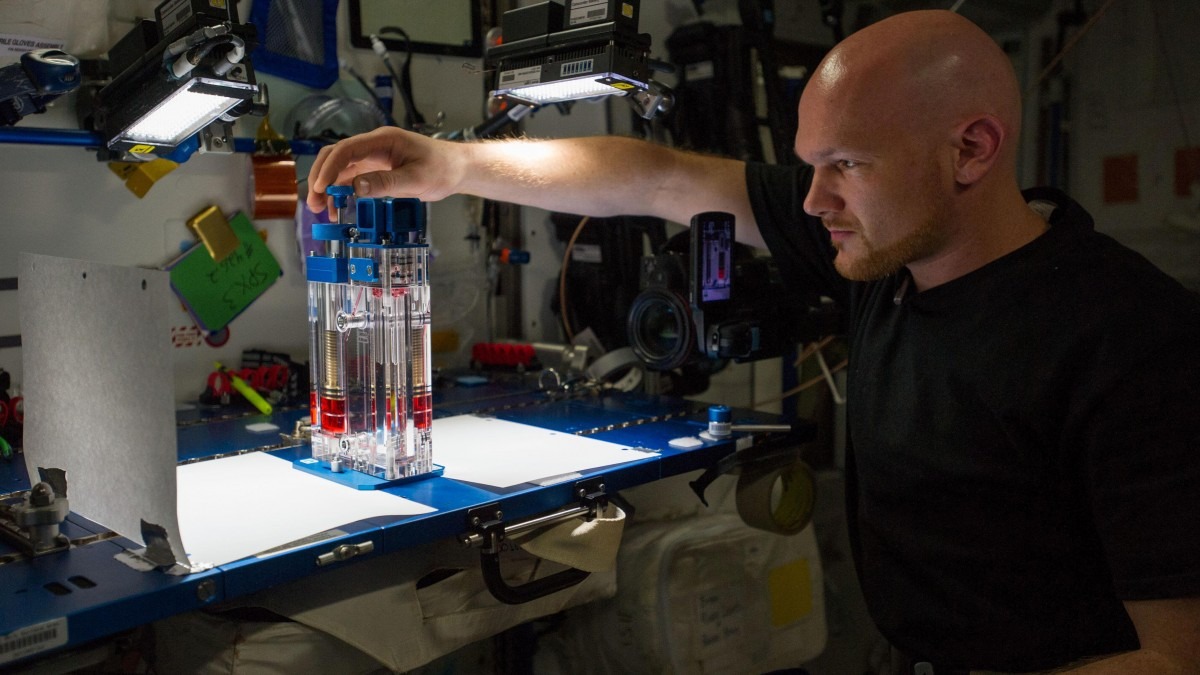

It wouldn’t be the first time that space exploration and medical science have been so closely linked.

From Hubble Space Telescope technology leading to a new digital imaging system for breast biopsies, to space shuttle materials providing better moulds for artificial arms and legs, space exploration has already helped us in many ways.

The next wave of exploration to Mars will likely benefit us here on Earth as well. It could be better online tools to manage your mental health, or a new way to stop people getting sick from radiation treatments, or something that we haven’t even thought of yet.

So, do you still want to go to space?

At the end of her lecture, Dr Tucker asked the audience again if they would like to go to space, now that they’d heard about the risks.

Surprisingly, around 70 percent still said yes.

Professor Reynolds explained that it’s this unwavering enthusiasm which will bring Mars exploration one step closer to becoming a reality.

“To make these ventures really successful what we really need, is for all of you to be prepared to go to Mars, in whatever devices and conditions we have,” she said.

“There are a lot of things we need to study. It is going to involve time, and lots of guinea pigs. So I am glad that you all want to go.”