This story sucks: could you learn to love parasites?

You can tell a lot about our feelings for parasites by the way we talk about them. To leech means to extort someone else, giving nothing in return. If you’re ticked-off, you’re annoyed or irritated. Worming your way into something is a sneaky and selfish act.

Professor Alexander Maier from the ANU Research School of Biology puts it more neutrally: “A parasite is basically an organism that lives on or in another organism and draws sustenance from that organism without giving anything back.”

Professor Maier studies malaria-causing parasites found in mosquitoes, called Plasmodium, so he knows all too well about the diseases they can cause. But this does nothing to dampen his enthusiasm for these bloodsuckers – so much so that he teaches an undergraduate course every year called Appreciating Parasites.

“We are primed by evolution to find them yucky, and to avoid them,” Professor Maier says. “But, if you look closely, you will find that parasites offer much more than at first glance. They can tell us so much about life in general.”

In fact, he believes that parasite appreciation is essential to science.

“If you don’t study and consider parasites, then you don’t understand biology.”

We can thank parasites for sex

One of the powers of parasites is that they shape evolution.

“Parasites actually provide solutions to things we are looking for, because of millions of years of co-evolution,” Professor Maier says. Many animals host parasites, so they evolve alongside one another, sometimes diverging into new species as they adapt around parasites.

“For example, there is a hypothesis out there that we wouldn't have sex without parasites,” he says.

Wait, that’s a big call.

But he explains that way back before animals had sex to reproduce, organisms would divide without any recombination of genes, meaning all individuals were exactly the same.

“Disease-causing organisms can adapt very easily to that,” Professor Maier says.

Organisms likely evolved sexual reproduction so they could have diverse genomes and become more resilient to threats like parasites.

“It’s a very efficient way of actually shuffling genes,” he says.

They can actually alter minds

The powers of parasites go beyond just physical discomfort. Some parasites can change the behaviour of their hosts.

We see this in toxoplasmosis, an infection from a protozoan parasite known for being common in cats. When animals such as mice are infected with the parasite, it can make them more reckless and fearless.

Another example is a particular worm that infects crickets.

“Crickets normally avoid water. But when the crickets are infected with this worm, the cricket suicides – it actually jumps into water deliberately,” Professor Maier says.

“Then the worm comes out, it releases eggs, and it infects aquatic life like dragonfly larvae. Then another cricket eats those dragonflies, that have developed into adults, gets infected, and jumps in the water again.”

It’s a warped circle of life, with the parasitic worm pulling the puppet strings.

Some parasites can heal you

“They’re not just an evil entity in the world, they actually have a purpose,” Professor Maier says.

While you may have heard of leeches being used in medical settings, other parasites are used to treat disease too.

“In a sense, parasites are nature’s pharmacy,” Professor Maier says.

Hookworms have been shown to cure people of their gluten intolerances, for example. It’s called worm therapy he says.

“People are infected on purpose with those worms. And then, after a while, they are exposed to more and more gluten. After a few weeks, they are able to eat a whole bowl of pasta.”

Another incredible part of that story is the attachment that people in the study felt towards their therapy worms.

One participant is quoted in an ABC article saying, “everyone in the trial called the worms our friends, so we don’t want them to leave us, but they do.”

Not only impressive, but inspirational

If healing abilities, evolutionary change, and mind-altering behavior aren’t impressive enough, Professor Maier says parasites have other super-abilities too.

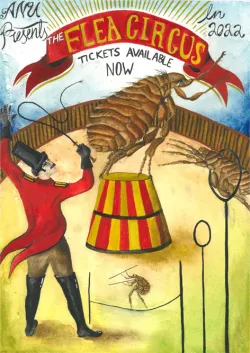

“If we were as strong as a flea, we could easily push a jumbo jet. If we could jump as efficiently as a flea we could jump over Telstra Tower, no problems,” says Professor Maier gesturing towards Black Mountain, where the tower watches over the ANU campus.

Changing our perspective on parasites will change science too, he says.

“In the past, and still today, most of our research is about disease, and how we can get rid of it (which of course is pertinent). But then we’ve also realised that parasites are actually much more than just the cause of disease. They are a really important part of the ecosystem.”

You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who appreciates parasites more than Professor Maier. But he notices a tangible change in people’s attitudes by the end of his parasite appreciation course, which is an intensive one-week immersion at the beautiful ANU Kioloa Campus (prime leech and tick habitat).

“I would say the transformation is almost like becoming a parent,” he says. “If you don’t have children, when you see a child throw up, you would normally turn and run away. But as a parent, you…,” he mimes enthusiastically catching vomit with both hands, “…to avoid the mess. And it’s a bit like that with people in the course.”

Just like catching your own child’s vomit, people turn towards the parasites they’ve come to care for instead of away. It has switched off the ick-factor.

After taking the course, one student reported: “I’m not going to lie, I now think they are quite cute, and I’m not sure how this happened.”

“Some people would even consider having parasites as a pet,” Professor Maier continues. “Me, for example: we have leeches at home.”

Pet leeches, you say? Even for someone on the journey to parasite-positivity, that’s a hard pass.

Could parasites leech their way into your heart? The course Appreciating Parasites: From Molecules to Ecosystems is offered in Spring by the ANU Research School of Biology.