Pearls of wisdom: what can a shell tell us?

For many thousands of years, pearls have been revered across cultures for their beauty and rarity. They can be found in ancient Chinese texts, in Hindu legends, inside a sarcophagus on display at the Louvre - and in the research findings of Dr Laura Otter.

A biogeochemist from the ANU Research School of Earth Sciences, Dr Otter studies nacre, the beautiful, iridescent coating you find on the outside of pearls and the inside of shells like oysters and clams.

While to most people, nacre’s value comes from its aesthetic appeal, to Dr Otter – and yes, she knows how apt her name is – it has an entirely different value: it can transport us back in time.

Nacre is created by the shell’s living inhabitant, the mollusc, which lays down microscopic layers of calcium carbonate alternating with organic materials like proteins, in a brickwork pattern. And it can, she explains, be analysed in the same way as a sediment core to reveal information about the environment it lived in.

“If we look at these layers in cross section, then we can go back in time, and reconstruct things like the water temperature, and see how the ocean temperature has changed. It’s super mind-blowing, really.”

In the ANU aquaculture lab, Dr Otter grows the shells in a stable environment, observing and measuring changes according to different conditions such as salinity, water temperature and the presence of trace elements.

“So then we have this this way of calibrating any wild shell,” she says. “After measuring, for example, oxygen atoms in the shell by looking at the ones grown in controlled conditions here, we can then know exactly what temperature a wild shell was at a particular time.”

Her research has revealed the impact of the changing climate on the mollusc’s nacre production, which is vital information for the pearl industry.

Increased carbon dioxide in the seawater, as well as ash runoff from bushfires, has increased acidity of the water, and affected the food supply for the molluscs. Changes like this affect the lustre and thickness of the nacre and reduces the number of pearls of gem quality.

“The pearl oysters are used to a very narrow window of environmental conditions and there’s been a lot of change for them in a really short period of time, and that’s scary.”

But it’s not only bad news for pearls.

“Because they’re filter feeders, oysters are considered the lungs of rivers or oceans so if things are not right, they suffer first. Their health is relevant to the whole ecosystem.”

As well as working with the pearl industry, Dr Otter collaborates across disciplines, including with biologists, and engineers who are interested in how molluscs can make a super tough material like nacre so much more easily than humans can, even with all our technology.

“I am always open to adding different facets to my research,” Dr Otter says. She thinks pearls are beautiful, of course, but her fascination with nacre as a material is holistic. “There’s just so much to discover.”

Her career in science began with a childhood fascination with dinosaurs, she says, when she was “mesmerised” by the idea of how whole stories about the lives of dinosaurs could be reconstructed just by studying their bones. It’s a passion she took with her to university.

Dr Otter has a visual disability, and is considered legally blind, which made fieldwork challenging for her as an undergraduate, she says.

“Climbing and scrambling about in odd terrain as a geologist in the field is a big barrier to accessibility and something we need to look at,” she says. “But nowadays I've adapted to how I do things, even if it was a bit of a learning curve to get there.”

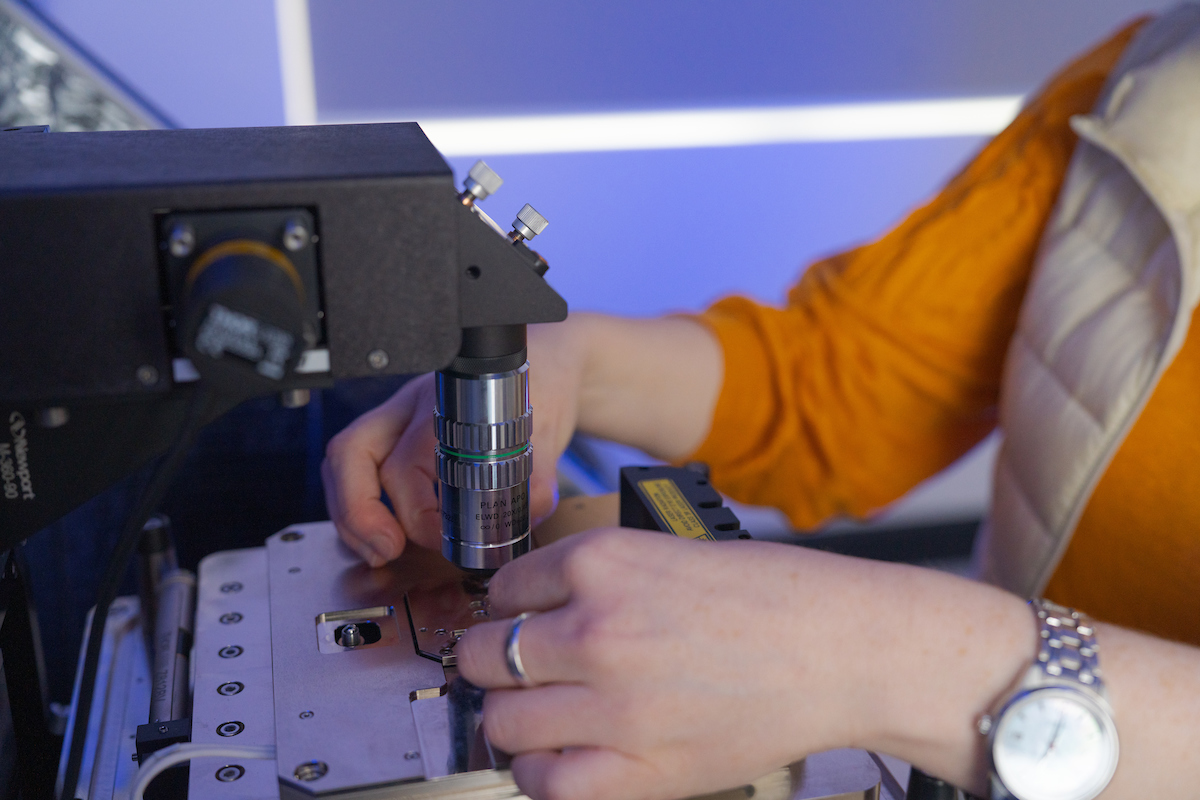

Dr Otter’s lab has just received a cutting-edge microscope, the first of its kind in Australia, which she helped to optimise for analysing biomineral samples like pearls and shells. An occupational therapist from Vision Australia assisted her with modifications which make it easier for her to use.

“You just need a bit of creativity, but with a visual disability you can still do things in most cases,” she says.

“At university, I never got to see someone with similar challenges have a great and flourishing career, and I want to be that person who other students see, and they’ll know you can figure things out.”