Let’s talk about sex. Beetle sex.

This is not the easiest work to explain to your family: you spend your days watching beetle sex tapes.

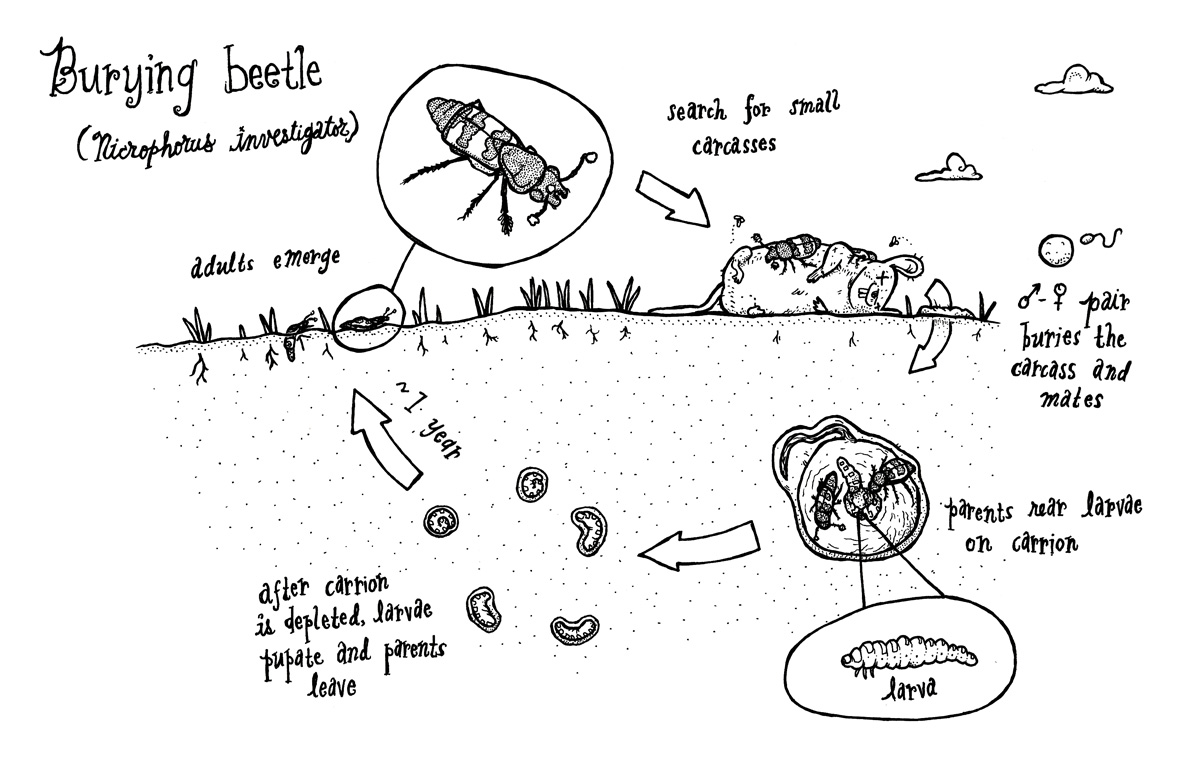

And this beetle sex is particularly… out there. British burying beetles are so called because they bury dead mice, which they then mate on, and use as a food source to rear their offspring.

This is the behaviour which Dr Megan Head from the ANU Research School of Biology previously observed via a camera link, and, she assures us, it’s all for science. Dr Head is learning how animals respond to a changing climate, in part, by studying the sex lives of beetles.

“The key to replenishing endangered populations is understanding who mates with who, and why they do it,” explains Dr Head, in a sentence which sounds familiar to anyone who’s ever read a gossip magazine.

She is focused particularly on how species differ in their male-female interactions and how they adapt to new environments.

Her answers are generally found by manipulating the environment of species with short lifespans, allowing her to watch evolution in real-time, to test out different theories. This is where the British burying beetles come in.

In an experiment worthy of Desperate Housewives: Beetle Edition, Dr Head had male burying beetles mate with a female in a box covered in the scent either of another male or one with no smell.

When males were sure that another man-beetle hadn’t been there before them to impregnate their beetle-mama, they were far more likely to care for the kids.

Understanding these relationships tells us how or if animals are going to be able to adapt to a changing climate.

If behaviours which help animals survive (i.e. natural selection), isn’t what impresses the opposite sex (i.e. sexual selection), there could be many impacts. This conflict between natural and sexual selection could change male-female dynamics, prevent adaptation, speed it up or slow it down.

For example, Dr Head and her fellow researchers found that increasing the sex-drive of male beetles led to female beetles being less able to care for their larvae.

“We did an artificial selection experiment, in which we selected males to have high mating rates in order to observe the impact on their parental care.

“It was actually quite costly to females, and that had a later impact on their parental behaviour because they experienced all these physical ‘costs’. They basically had no energy left to invest in their offspring, and were less caring as a result.”

In this instance, if the males who were thriving in a changing climate also happened to be the males with higher libidos – there could be direct consequences for the breeding habits and population of burying beetles.

Whether she is studying burying beetles, eucalypt beetles or fish, however, each of these species provide a vital link in their fragile ecosystems. The burying beetles, for example, don’t just enjoy sex on mouse carcasses, they have an important role in their ecosystem, decomposing the dead mice back into the soil.

It’s only by studying the entire ecosystem that we develop a broad understanding of what global climate change is doing to our animals, food supply and the natural world.

For burying beetles, this means their private life will remain very much front-page news, but this is at least one sex tape which is in the public interest.

This article was originally published on ScienceWise, a blog supported by the Australian National University.