Isolation salvation

When the COVID-19 crisis hit, The Australian National University underwent rapid and radical change. Our teaching went online, the campus was closed, and our laboratories were only accessible to those researching COVID-19 or supplying protective equipment to medical staff.

In our homes, ANU researchers, staff and students have set up makeshift workspaces with monitors perched on piles of books, home-schooled children on our knees, and grateful pets at our feet.

Amid the chaos of the COVID-19 isolation, we found salvation in the little things. We reached out to our science, health and medicine community to find out what helped them survive isolation.

Professor Celine D’Orgeville

Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics

It’s not surprising that Professor Celine D’Orgeville has exhausted her puzzle collection during lockdown: assembling complex things is her forte.

Professor D’Orgeville is leading a project to assemble a telescope unlike any other in Australia, one which manoeuvres space junk with a laser.

When the ANU Mount Stromlo Observatory closed, it was a major setback for Professor D’Orgeville and her team.

“Before the lockdown we were in the final phase of assembling it, then trying it on the sky.”

“For the moment, the telescope has just been put on hold.”

In the early stages of isolation, Professor D’Orgeville looked to a long-held pastime to alleviate the stress of the growing COVID-19 pandemic: puzzles.

There is a nearly-finished Christmas-themed puzzle laid out on a table on her deck.

“It's my fifth 1000-piece puzzle since we started working from home,” she says.

Now Professor D’Orgeville is facing a new challenge. She has run out of puzzles.

“Can I ask you to include something in your story?” she says.

“Could you ask if anyone wants to trade their puzzles with me?”

So Canberrans, if you’re like Professor D’Orgeville and have a large puzzle to trade, she can be contacted at celine.dorgeville@anu.edu.au.

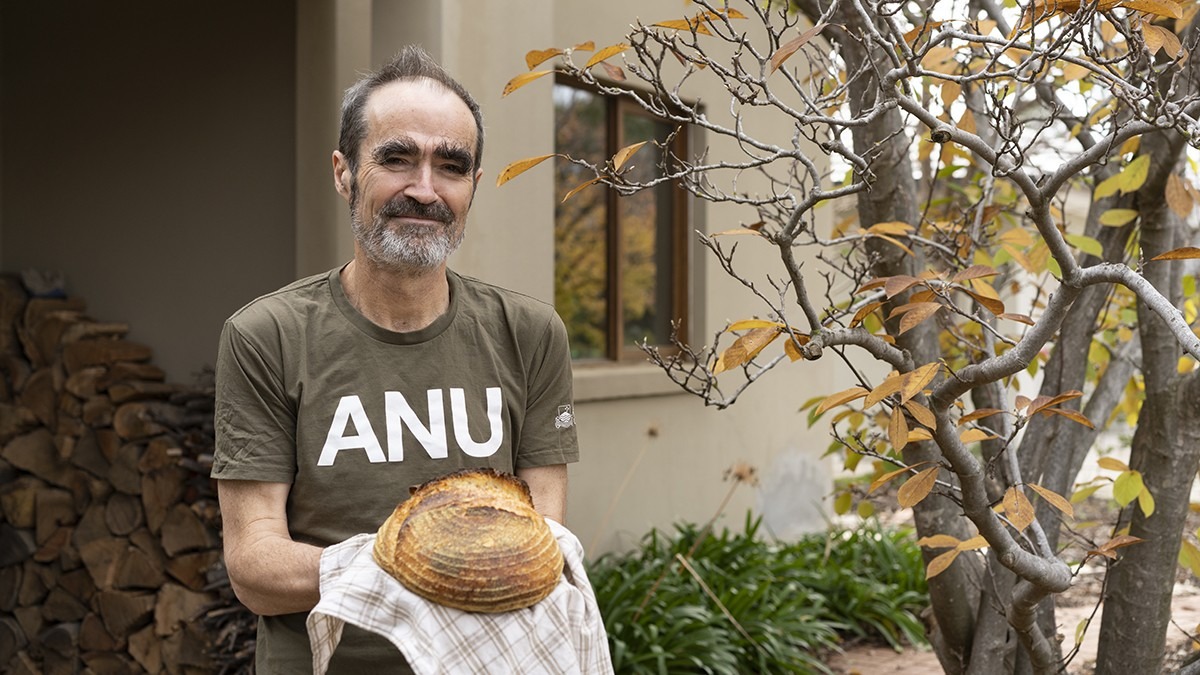

Professor Kiaran Kirk

Dean, ANU College of Science and Medicine

“I’m a self-confessed bread tragic and I do have a thing about bakeries,” says Professor Kiaran Kirk.

“When I travel to another city, and need to find somewhere to stay, I will often google terms such as ‘sourdough’, ‘artisan bakery’ or ‘best bakery’ to find out where the best bread is to be found. Wherever it is, I try to find a hotel nearby.”

While Professor Kirk relishes the perfect sourdough loaf on his travels, he enjoys baking his own sourdough even more. The lockdown has been an ideal opportunity to work on his recipes.

As you’d expect of a biochemist, Professor Kirk approaches sourdough baking with scientific attention to detail. Under lockdown, he has run some experiments.

“I’ve been experimenting with different proportions of water, different sorts of flour, different fermentation times, different additions – grains, seeds, fruits,” he says.

When I arrive at Professor Kirk’s home, two fresh sourdough loaves are swiftly pulled from the oven. The kitchen is filled with the smell of fresh bread as the golden loaves sit steaming on the bench.

“What is the best way to enjoy it?” I ask.

“I love sourdough toast,” he replies. “Sliced thickly, and spread with butter and my wife, Julie’s, home-made jam.”

As I leave, Professor Kirk wraps one loaf in a tea towel and hands it to me. He rushes off to a Zoom call and I rush home to cut myself a slice.

I bite into the thick crust and it crackles between my teeth. The bread inside is soft, stretchy and flavoursome; it could only have been crafted by a biochemist. Three slices later I’m ready to get back to work.

Professor Adrienne Nicotra

2020 has presented a number of hurdles for Professor Adrienne Nicotra’s lab. She’s standing in her back garden next to a makeshift greenhouse full of seedlings as she describes the first.

“We were growing these on campus for an experiment on the ability of alpine plants to respond to climate change.”

The hailstorm that hit Canberra in January shattered the roofs of the ANU greenhouses.

“When we had the hailstorm, we had to scrap the experiment and restart from seed.”

Professor Nicotra’s lab was able to start the experiment again using growth chambers on campus. But it wasn’t long before a global pandemic presented the next hurdle.

“When the campus closed we had to end the experiment again. We tried to take home any plants that we could, so I brought these guys home,” says Professor Nicotra as she cradles a bluebell in her hand.

“I’m trying to get them to seed so we can start the experiment a third time.”

Professor Nicotra says she prefers to have the plants with her at home.

“They've been great for my mental health. When I get tired of Zoom, I can come out here and play. I don’t usually get to spend so much time with the plants when I’m on campus. The Plant Services staff and other lab members look after them.”

I ask Professor Nicotra if this has taken her back to her roots.

She sighs and turns away. I realise it’s time for me to leaf.

Melanie Pill & Meena Sivagowre Sritharan

Mel and Meena are well-practiced at sharing. When they were on campus the two PhD students shared an office at the Fenner School of Environment and Society. Not only that, they live together in a share house where they share cooking duties, a (growing) collection of plants, a veggie patch and the occasional bottle of wine.

The share house is where I meet them. They come to their front gate each carrying a plate of treats. Meena is a plant ecologist. She tells me how lockdown has affected her research.

“Working from home as a PhD researcher has been a little tough,” she tells me.

“As a person who has a short attention span and loves the outdoors, being restricted to your home was really hard.”

“It helps that I’ve really upped up my cycling game. I’ve been exploring new cycling tracks that I didn’t know existed,” she says.

Mel’s field of research is climate change-related loss and damage. Sharing the house with Meena has helped her to continue her research during lockdown.

“I’ve been blessed to stay with my simply amazing housemate, Meena. We both motivate and distract each other.”

Regular exercise has been important for Mel too.

“I’ve realised that you don’t need to pay for a treadmill at the gym when the Inner North wetlands are just around the corner for a jog,” she says.

I cast an eye towards the plate of banana muffins and ask what hobbies have kept them busy.

“Having time to bake has been one of the unexpected advantages,” Meena says.

“We’ve been baking, cooking, and trying all sorts of food from vegan shortbread cookies to Tsoureki, German potato dumplings and homemade noodles.”

I accept a banana muffin from Mel and a shortbread cookie from Meena. Since they are so good at sharing.

Dr Robert Schmidli

ANU Medical School

Dr Robert Schmidli meets me at his front door and ushers me into his living room. Only… it doesn’t look like a living room right now. It looks more like a recording studio.

In one corner sits a sparkling grand piano. Placed around it are microphones, lights and a number of cameras on tripods.

Dr Schmidli, who is an endocrinologist at the ANU Medical School, is a classical pianist in his spare time.

“I do about a dozen public concerts a year,” he tells me.

While some concerts are held here in his home, others are with his piano club, for charities or at the Wesley Music Centre.

“My opportunities to perform were curtailed when the lockdown laws were introduced,” he says.

In spite of the restrictions, he wanted to keep performing for his friends. That’s when he thought about recording himself.

“I had the gear and I thought, ‘Well, I've got to practice for something. Otherwise, I’ll just let it go.’”

Dr Schmidli created a YouTube channel and started uploading his videos. He distributes his videos on his social media channels and by email.

I ask Dr Schmidli if he has any favourites.

“Absolutely, yes. Beethoven. But I've got others as well. I'm doing a lot of Chopin for these recordings because he's written a lot of short pieces. They are very popular and go down well with my audiences.”

To join Dr Schmidli’s audience, you can find his videos here.

Professor Saul Cunningham

Fenner School of Environment and Society

Some people aspire to having a carbon neutral household. Others might aspire to having carbon neutral transport. But Professor Saul Cunningham isn’t here to mess about.

He is bringing carbon neutrality to letterboxes.

In fact, Professor Cunningham has taken it one step further, designing a letterbox that he claims is carbon negative.

Although I’m well aware of the Professor’s environmental credentials as Director of the ANU Fenner School of Environment and Society, I’m sceptical. I ask him to explain.

“The previous letterbox was damaged by a reversing tradie,” he says.

“Lockdown was the opportunity that we needed to renovate it.”

A sustainable approach was critical for the crafty Professor.

“First we sourced the letterbox itself from the Green Shed,” he explains.

“Then we drew design inspiration from across the globe. With this letterbox we have referenced the vertical forests of Milan’s skyscrapers and the rooftop farms of Hong Kong.

“What we’ve done is to grow mosses and succulents on the top of the letterbox. The mosses sequester carbon from the atmosphere.”

Professor Cunningham gazes proudly at his letterbox.

“I’m very excited about the moss. It has settled in beautifully.”

I ask if the letterbox is the first of its kind.

“We stole the idea from our neighbour. Now we know of three carbon negative letterboxes in our neighbourhood.”

Carbon negative letterboxes, it seems, are a growing trend.

Erin Parker

Research School of Psychology

Erin Parker knows all about how lockdown is affecting our mental health. Erin, who is completing her PhD at the ANU Research School of Psychology, also works as a psychologist.

I have come to meet Erin at her bedroom window. After lifting the catch on the gate, I walk up the driveway to find the large window framed with an array of small house plants.

She sits with her dog Pepper while she talks to me.

Since the lockdown began, Erin has seen how people have dealt with the loss of activities that are important for their wellbeing.

“They can't go to the gym. They can’t see their friends. They can't do things that they usually use to maintain their mental health.

“A lot of people are really down on themselves and feel that they're not coping.”

Erin knows this feeling.

“There are still some days when I get down on myself as well. I feel like I should be more productive. I should be doing more.”

I ask how she copes on these days.

“I'm a lot better at catching those thoughts now and knowing what to say to myself.

“It’s been important to make my space at home a pleasant place to be. I love having these plants – I have about 50 of them. I think that's one of the things that's been keeping me sane. And being able to get outside for a walk with my dog.

“But sometimes you just need a day in bed. And that’s OK too.”

Professor Russell Gruen

Dean, ANU College of Health & Medicine

Professor Russell Gruen has always loved dogs. Throughout his childhood, his family bred Beagles. And when his career as a surgeon and university professor took him all over the world he’s always been accompanied by a four-legged friend.

When I meet Professor Gruen at his home, there’s a four-legged friend by his side, Bailey.

Bailey is no stranger to travel, having migrated from Singapore to Canberra when Professor Gruen became Dean of the ANU College of Health and Medicine in early 2019.

He greets me with a suspicious growl, but soon accepts a gentle scratch behind his ears.

“Bailey is able to express a full range of emotion through the position of his ears and his eyebrows. We’re pretty good at understanding each other,” says Russell.

Russell explains that Bailey, who is a cross-Schnauzer and Jack Russell, has boundless energy, plenty of affection and more than a bit of anxiety.

“He’s always present. He sits alongside me while I work, at my feet when I eat, and next to me on the couch when I read. He takes me for a walk every day, and he waits eagerly at the car in anticipation of our next adventure.

“Bailey’s loved having me home, I’m sure of it. But truth be told, I’m also very glad he’s been around. Having some routine with a quarantine buddy has definitely helped me face some of the challenges that have come with working off-campus.

“He’s a bit of an old hand, too. He quarantined for 10 days on his way over from Singapore so he’s probably wondering what all the fuss is about.

“At the moment, I’m preparing us both for the return to campus.”

Bailey cocks his head.

“This year keeps throwing us curve-balls, but we need to get on with the recovery.

“And sorry Bailey, you don’t have the right skill set. You’re going to have to keep working from home.”