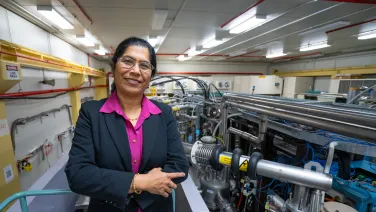

In conversation with Professor Melanie Campbell, a trailblazer in physics and rights for women in science

Professor Melanie Campbell is known for developing improved understanding of the eye’s optics and high-resolution imaging of the retina at the rear of the eye. Currently she is developing light-activated treatments for eye disease and non-invasive imaging techniques for the detection of Alzheimer's disease at University of Waterloo, Canada. Professor Campbell was the first woman to graduate with a PhD in applied mathematics from ANU.

The joint conveners of ANU Women* in Physics, Astro and Engineering, Dr Noemie Bastidon and Dr Julie Tournet, both researchers at the ANU Research School of Physics, joined Professor Campbell in conversation to discuss how she navigated her successful career in academia and advocated for women’s rights in universities along the way.

From negotiating the first-ever maternity leave at CSIRO and juggling a young family as an academic, to her roles in university equity and diversity leadership, Professor Campbell generously shares her experiences as one of the few women amongst her peers.

Dr Julie Tournet: We're very honoured to be talking to you. We have followed your career at the University of Waterloo, and we're happy to hear your experience because you've been pioneering woman's rights in science in university environments.

Professor Melanie Campbell: I've been trying. It's an ongoing struggle.

Dr Noemie Bastidon: What was your journey like?

I went to the University of Toronto, where I ended up doing Honours in Physics. I had a wonderful mentor. He really understood issues around minorities and inclusion.

I did a coursework masters at the University of Waterloo. Then I never wanted to do another course again because I'd done seven courses and researched and written a thesis in 16 months!

At that point, in order to be more research intensive, I could go to ANU, New Zealand or Great Britain − they had Commonwealth scholarships. But the rules in Britain really annoyed me, so I didn’t apply there.

Dr Bastidon: Why?

Because if I were male, they would pay for my wife to travel. If I were female, they would not pay for my husband.

Dr Bastidon: Woah, has this changed?

This was many years ago. But Australia would pay for your spouse of any gender. I applied to Australia for a Commonwealth Scholarship. ANU saw my application and contacted me separately and offered me an ANU scholarship.

Dr Bastidon: Were there any women professors?

No, none at all. The women had to fit in, and it was so blatant when I think back. At Waterloo and later at ANU they would say they were just going to treat me like one of the boys. In some ways that was fine. But it seemed very odd that they didn't understand that this was not the way that they were going to get more women in physics!

Dr Tournet: So you stayed at ANU for how long?

It took me almost five years to finish. I had viral encephalitis partway through and had to take six months off.

I went to the applied mathematics division, then I got cross-appointed to physiology at the John Curtin School of Medical Research. That’s when I became truly multidisciplinary. I actually got a PhD from both departments in the end. Then I got a CSIRO postdoc, so I stayed for that.

Dr Tournet: We hear a lot about the ‘two body problem’ in academia. Because my husband accompanies me around the world, we get lots remarks from people. Did you also experience that?

Oh, absolutely. My husband was certainly supportive, but my supervisor was puzzled. My supervisor finally came to me one day, and said, ‘I just don't understand’. For a husband to follow the wife and not have a job lined up, that was incomprehensible to my supervisor. He said that the other way around was fine. He wouldn't have thought of himself as sexist, and yet he just finished saying something extremely sexist.

Dr Bastidon: How was it when you were pregnant?

When I had my first child, it was while I was a postdoc in Australia. After I told my supervisors that I was expecting, I was informed that my lab was being moved to the basement. I couldn't help but feel that the two things were connected. I wouldn’t be able to do the experiments I’d planned. I thought maybe it's time just to put your head down and not make a fuss. You're very vulnerable at that time, you can very easily lose your self-confidence.

Dr Bastidon: Was there any parental leave?

Oh no! I actually negotiated the very first parental leave for someone on a CSIRO postdoc. I’m very proud of this.

CSIRO was great about it. They just said, tell us what you want and we'll make it happen. I ended up with six or eight weeks of full-time leave, and then six months, part-time. I was thrilled.

Dr Tournet: How did you navigate those years with young children? When you're caught up in your crunch time of research, it's hard to be home. We’re both young mothers, so this is on our minds!

I had a lot of trouble because I'm a morning person. If I had a really a long day then a really rough time with the kids, then I still had things to do afterwards. It was tough.

We were lucky to have a crèche on campus at ANU, and I breastfed on demand while at work. I had asthmatic children as well, so that was difficult at times.

I still remember very vividly one occasion at Waterloo, the annoyance of my Chair that I was taking leave when I had my second child. If you want people to act equitably it should be the central administration that takes on the cost of equity things, not individual departments.

Dr Bastidon: Would you say that how you were perceived as a professional changed after you had children?

Definitely. There were people who assumed that was it; that was the end of my career because I was having a child. One day I ran into my Master's supervisor while I had two children in tow and he assumed that I was no longer in academia.

Dr Tournet: There’s this judgement that if you're a parent, then you're not a good professional, and that if you're working full time, then you can't be a good parent. You're always on this line where you're trying to just do the best you can.

Yes!

Dr Tournet: What would you say is the biggest policy change that really made a difference for you in the workplace?

The biggest one that I'm proudest of, is the one I fought for. And that was for a parental leave top-up for spouses that matched the maternity leave and parental leave for birth mothers. I was on the university faculty committee that used to hammer out issues. I remember saying, ‘You can make the argument that men don't need maternity leave, but you can't make the argument that they don't need parental leave’.

Dr Tournet: So how did things change? Since you've been at Waterloo?

Oh, bit by bit. Over the years things have changed, but quite slowly.

Now one of the issues we have is with violence and sexual violence. It’s horrible.

It is very difficult, and how these types of cases are handled still isn’t approached with the victim’s best interest in mind in much of Canada.

Dr Tournet: How can we navigate these issues better?

First of all, education. That's where University of Waterloo and other universities have most recently invested a lot more money and staff, such as into training and dissemination of concepts and ideas; trying to change the way people think about things.

Last year I helped to organise a couple of Bystander Intervention workshops: one for the students in physics then one for the faculty to help them to be prepared for a difficult situation.

Dr Bastidon: Do you have any advice for women in STEM?

You can't do it by yourself. So having groups and conferences is really useful. I spoke at one of the first women in physics conferences, and people were in tears. They were in tears just because they hadn't been in such a supportive room before. It was astounding. It was a life-changing event for me to realise how much impact it could have.

Dr Bastidon: It provides lots of fuel to keep going.

I try to pick doable projects where I can make a difference. You can't do everything and if you try, you will potentially stretch yourself too thin.

You will also find allies and you will find them in unexpected places.

I remember running into a Vice President at the University of Waterloo after a committee meeting about parental leave where I was representing the faculty association. And he looked at me and he said, ‘You can't tell which side we're on.’ He was one of those unexpected allies. It was he and I against the rest of the committee.

Dr Tournet: Thank you so much for everything you have shared. It was really inspiring.

I hope so. But remember, you shouldn’t feel you have to do it all!