Calling all puzzle fans: do you have what it takes to work in cryptography?

If you look at the original design for the Hanna Neumann Building on University Avenue, it has four floors, which is more than enough space to house the ANU Mathematical Sciences Institute and the ANU School of Computing.

So why does the building we see on campus today have five floors? And what, exactly, goes on up there?

“We’re quite open about what we do,” David Jamieson says, sitting in a meeting room on the fifth floor. “There is signage.” He pauses. “But it is true that most of the signage is in code.”

David is a cryptanalyst with the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), an Australian Government agency focusing on national security and foreign intelligence. Their motto is “Reveal their secrets. Protect our own.” And they occupy level five of the Hanna Neumann Building.

The partnership between ASD and ANU came during the design process of the building, as did the agency’s $12-million investment to add the extra floor. Now it is home to the Co-Lab, a collaborative research space where ANU academics and research students work together with ASD staff like David on problems related to national security.

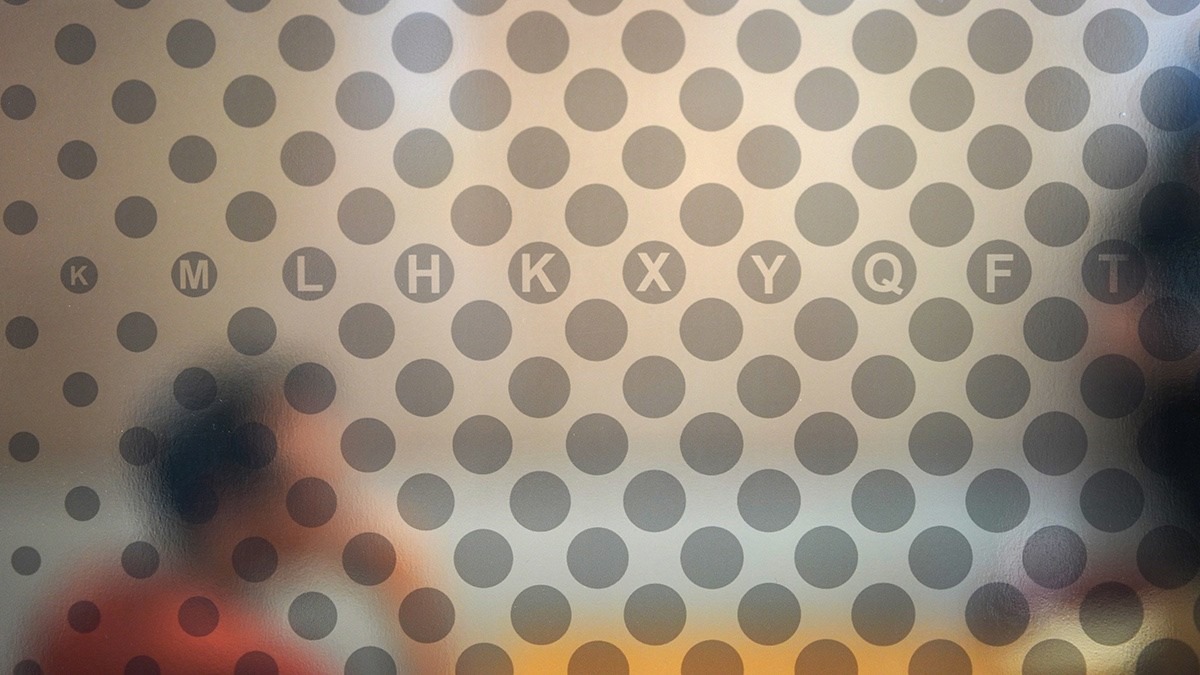

The doors to the Co-Lab welcome you with patterns of black circles and squares - the coded signage. The glass wall of the fifth-floor meeting room also features what look like random letters scattered throughout the decorative pattern on the decal. (They’re not random.)

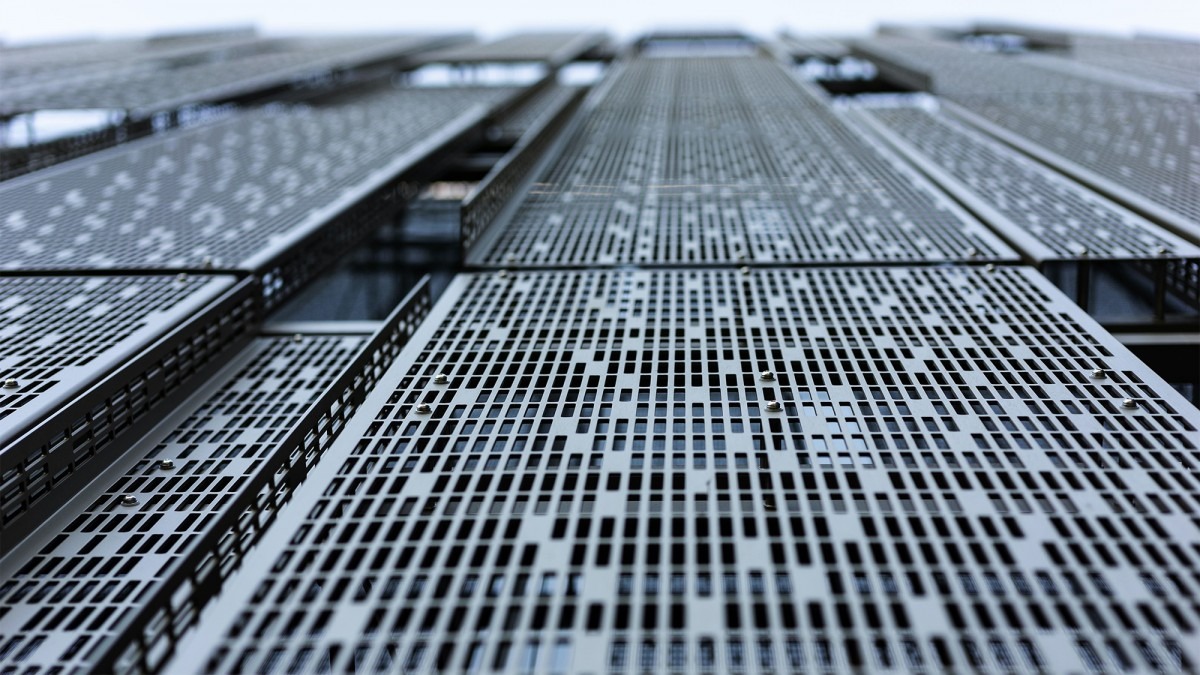

Similar codes are located on all levels of the building, and even on the exterior. David says they connect together like a puzzle to form a larger message. As far as he’s aware, it hasn’t been broken.

The puzzles, in their way, announce the presence of ASD in the building, but seem strangely incongruous when you think about the high-stakes, high-tech work ASD does, like hacking into and destroying the IT and propaganda networks of Islamic State. But enticing people with puzzles actually works exactly the way that ASD want.

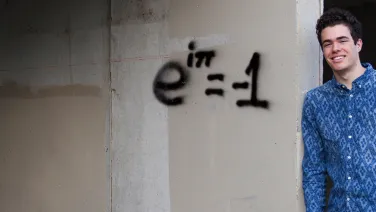

“Cryptography is a puzzle, right?” David says. “People solve Sudoku or crosswords or cryptograms for fun and, in some ways, the skills you need to solve those puzzles are the exact skills that you need as a classical cryptographer.”

And ASD needs cryptographers.

Famously, British codebreakers were recruited via a cryptic crossword to the wartime project of cracking Germany’s Enigma machine, and David says this method wouldn’t work too badly today either.

“The process of peeling away the puzzle in a crossword is similar to the process of codebreaking.

“When you're codebreaking, it's not like you suddenly flip the switch and the whole thing falls out instantly. You have this incremental, tiny insight into one part of the code, and then the breakthrough comes from being able to recognise the larger picture from that little insight you get, in the same way that getting a single letter in a crossword can be a huge breakthrough.”

The major skillset which distinguishes the modern codebreakers from those of history is, of course, to do with technology.

“Now a huge part of the discipline is not only understanding the mathematics, but being able to implement that mathematics on a computer, to get as much juice out of the computer as you can,” David says.

“The code is no longer just covering words, it’s covering enormous chunks of data in zeros and ones. So the field is infinitely more complex, but the goal, and the mindset, are fundamentally the same. You still need that same childlike exploration of ideas.”

Undergraduate maths students who fit the bill can apply to complete summer research and Honours projects at the Co-Lab, with a view to future work at the agency. Once they receive baseline security clearance, what they’ll find inside looks much like any public service office.

“What you see here is people hard at work on their projects,” David says, “but it’s not usually silent. The kind of space we work in is huge and interconnected, with people who are genuinely enthused about what other people are working on.

“They’re all contributing something in an inter-related way to the big picture of ASD and working towards the same goal.”

Cryptography is just one area of research available to students, alongside number theory, statistics, data science, secure systems, and vulnerability research.

“It really doesn't matter what your field is,” David says. “You just need the drive to really deeply understand something.

“It would be more or less useless to have a cookie-cutter approach to developing people who do intelligence work. You're explicitly trying to solve problems that your adversaries don't think are possible, and part of that means you're trying to solve problems that no one else has solved before. Generally, that requires you to be able to think quite uniquely.

“You have to have a certain intellectual curiosity to not just understand what you’re told but to have a desire to push yourself beyond that to some deeper abstract level.”

It’s the kind of curiosity which might help someone to crack the code written into the building itself, for example. Or, just perhaps, to ask why the elevator for that same building has a button for a non-existent level six. Surely, that’s where the real secrets are kept?

“No,” David says. “That is just the roof.”

ASD recruits clever, curious, creative people who seek to make a difference, with opportunities ranging from linguists and analysts, to cultural experts, to cyber security and IT specialists. Find out more on the ASD website.