We’re going on a beetle hunt

When scientists observed snow gums dying in huge numbers, they immediately suspected a beetle might be the culprit.

The next step seemed easy: catch some beetles.

But this is a story about what it’s like to tackle an entirely new problem, so nothing is easy.

Not even catching some beetles.

An interesting beetle

The first time Dr Matthew Brookhouse saw the beetle which would soon consume years of his life, it was 1998.

He was working in forestry in Victoria at the time, supervising a native forest inventory, when he noticed unusual c-shaped grooves in the bark of a couple of trees.

"We were with a contractor who had been working in the bush for decades, and I asked if he knew what caused them," Dr Brookhouse remembers. "And he said, 'It's some insect but nobody really knows.'"

Dr Brookhouse asked the contractor to cut out a section of the affected area. He took the large piece of wood back to his office in Melbourne and sat it on his desk.

"Then one morning I came into the office, and there was this dirty, huge longicorn beetle sitting right on top of it.

"And that was actually how it all began."

The longicorn beetle, or Phoracantha, in Dr Brookhouse’s office was not an invasive pest, as you might expect.

It was a native borer whose larvae feed on live wood, effectively ringbarking the tree in the process.

He noted the beetle. It was interesting, but it was not a particularly significant beetle to Dr Brookhouse.

Not yet.

The a-ha moment

Dr Brookhouse had left forestry and moved into academia when he crossed paths with the beetle again.

It was 2018 and he was now at the Fenner School of Environment and Society at The Australian National University, when the NSW Department of Primary Industries reached out to him about some “unusual observations” they’d made.

In parts of Kosciuszko National Park, snow gums were dying.

"We got out there, and as we were walking from the car, I was gobsmacked," Dr Brookhouse says.

"Upslope from us in the main valley, you could see every tree was either entirely dead or quite obviously on its way out."

The mountainside was a graveyard of skeleton trees. The leafy canopy was completely gone, the usually majestic snow gums reduced to nothing more than sticks.

And there, on the trunks of the dead trees, were the same distinctive marks he’d seen on his desk twenty years earlier.

It was the work of the Phoracantha beetle.

It was the wrong kind of a-ha moment for a scientist: the sudden discovery of a shocking problem.

They cut a section from one of the trees and took it back to ANU campus. Dr Brookhouse wrapped it in mesh, stored it in a room, and waited.

Eventually, what he was waiting for occurred: two beetles emerged from the wood. And they were longicorns, just as he suspected.

But they were actually two different species of longicorn. One was Phoracantha longipennis (yes, really) and the other was Phoracantha mastersi.

As that contractor had indicated all those years ago, nobody knew very much about this insect. How could work start on this urgent problem if they didn’t even know which species was the culprit?

They were going to need more beetles.

Meet Eve

Dr Brookhouse began to develop strategies to survey and identify the insects causing the dieback.

He found that the larvae infestations would start high in the branches of the snow gums and then work their way down through to the base, sucking the life out of the tree from the inside in the process.

Together with his Honours student Jozef Meyer (who uses they/them pronouns), Dr Brookhouse identified trees in Kosciuszko National Park which were still alive but had clear evidence of the presence of the wood-boring larvae inside.

And on them, they set two different kinds of traps, ready to collect any beetles as soon as they emerged from within the trunk.

Then they sat back and waited for their beetle bounty.

But it never came.

They checked every single trap they had set, on every single damaged tree, and all they ended up with was one single beetle.

"We were just happy to have something!" Dr Brookhouse recalls. "Jozef and I were hugging each other, saying, 'We got one! We got one!'"

They named their first and at that point, only, trapped beetle Eve.

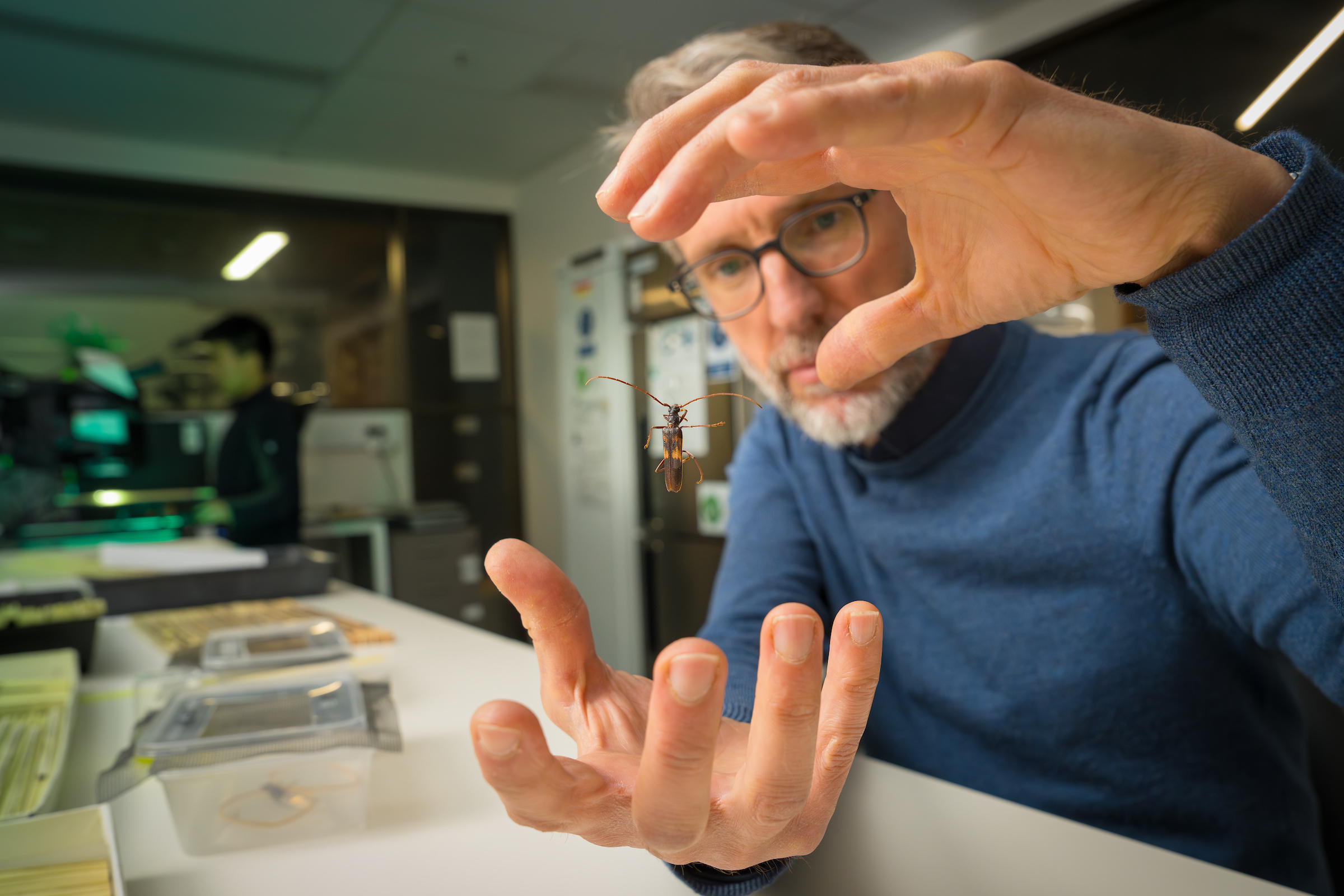

"And here she is."

Smiling like a proud parent, Dr Brookhouse opens a wooden box he keeps in his lab, revealing a beetle pinned to a display board.

But clearly there were many, many more Eves out there, somehow eluding them.

This was going to be more difficult than they thought.

Dr Brookhouse and Meyer dug deep into the literature on the mysterious Phoracantha, to try to crack the case.

They even spoke to one of the world’s leading Phoracantha experts, Professor Larry Hanks, an entomologist from the University of Illinois – who also happens to be the brother of Tom Hanks.

"He helped us with some of the research directions," Meyer remembers. "Yeah, and he sounded exactly like Tom Hanks!"

Then, the following summer, Dr Brookhouse and Meyer returned to the national park not only to start again, but this time, to up their game.

"We deployed every method we had," Dr Brookhouse says.

"And we were not going to stop until we found them."

Let the beetle hunt begin

The researchers took their traps back into the mountains, now including UV light-trapping tents, to hopefully lure the beetles in.

They also committed to going out on foot every night, equipped with head torches and spotlights, to scan trees for beetles as they emerged from inside.

Setting themself up in a lodge, Meyer spent their days checking traps at ten different sites.

Then every night, they would head back out into the bush with their torch, looking up and down tree trunks for a beetle the same colour as bark, until midnight.

Then they’d do it all again the next day. And the next.

And day after day, night after night, they found... nothing.

All around them, every single tree had clear evidence of the presence of these beetles and yet, where were they?

"It got to the point where I started to get a bit crazy," Meyer recalls.

"I was doing the same thing every day, not seeing what I thought I was going to be seeing.

"It was cold and it was wet and there were some dark moments, for sure."

But Meyer kept the promise to not give up, with Dr Brookhouse joining them for stretches of time.

"Every evening, we’d convince ourselves that this was the night!" Dr Brookhouse remembers.

"We'd say, 'This is going to be a good one! The conditions are just right!' And then slowly, over the course of the night, the mood would dampen, and then it would turn to desperation."

They would end most nights by driving around the lodges at Perisher, dejectedly checking every light source for signs of beetles.

There were no signs.

"It was pretty funny," Meyer says in that way where it's not actually funny but you have to laugh, right?

"It was incredibly insulting!" Dr Brookhouse says. "The beetles were clearly all around us and we couldn't lay our hands on a single one of them."

While Meyer was checking traps, Dr Brookhouse passed the daylight hours sorting through wood piles at the ski resorts, "day after day, just moving wood around" thinking perhaps the beetles hid in there during the day.

"They don't!" he says, emphatically.

But he only knows that – now – because he checked.

You hear a lot in science about making new breakthroughs. You don’t hear so much what it took to get there.

Maybe because this is what it looks like: a scientist moving around piles of wood.

"Anyone who's involved in researching a new problem is familiar with, at times, beating your head against the wall," Dr Brookhouse says. "And feeling like you're not getting anywhere."

But you need to understand a problem before you can work out how to fix it.

You have to start somewhere.

Meyer continued the relentless hunt for the beetles – which were all around them, but nowhere to be seen – for over a month.

It felt longer.

In late January of 2021, another student, Josh Coates, joined them in the field.

"Back here in Canberra," Dr Brookhouse says, "the wind was up, it was really warm, and I remember thinking, 'Ooh, this is a good night for it.'"

He'd thought this many times before, of course.

But on this particular good night up in the mountains, while Meyer was busy setting up a light tent, Coates went for a stroll in the nearby bush.

Then, like it was no big deal, Meyer heard Coates casually call out:

"Hey, is this the beetle you’ve been looking for?"

Sitting right there was the first Phoracantha they’d seen since they’d started the fieldwork.

In Canberra, the text message came in on Dr Brookhouse's phone:

"We’ve got one."

Over the next two weeks, more and more beetles appeared.

"I remember saying, 'It's real! They’re here! We aren’t crazy!'" Meyer laughs.

"It was an exciting moment. I mean, we weren’t happy they were there. But we needed the data to show it was an actual problem."

Thinking like a beetle

"From that point," Dr Brookhouse says, "what we've discovered is that you can trap all you want, and you might pick up an insect if you’re lucky.

"But the only way that really works is to go out there at night with torches and look for them."

And most importantly, because they had spent so much time coming to understand the conditions that didn’t bring the beetles out, now they knew exactly the conditions that did.

"Now we don’t kick off before 9:30pm, and if the temperature at that time is less than 12 degrees, then we don’t bother going out,” Dr Brookhouse says.

"If you get two days of warm temperatures in a row, with a bit of cloud cover? That’s ideal."

After four years of insect collections, their modelling can predict the emergence of beetles down to the day.

"This year we predicted that the emergence would begin on January 12. On the night of January 12, one of our PhD students found three beetles."

That was the start of what Dr Brookhouse calls this year's "amazing emergence", with a research assistant going on to collect 85 beetles in one single night. It's a world away from that first year with Meyer.

"The beetles just came out in huge numbers,” Dr Brookhouse says.

"It was fantastic because it showed we've nailed this: we know where to go; we know what to look for in terms of visible signs on individual trees; we know exactly when to go."

"It's affirming," Meyer says.

"We needed to do all that work. That's what ecological research is: you need to spend time in the place to observe it."

"That's what it takes," Dr Brookhouse says.

"But my goodness, this is a real problem.

"And it's just getting worse and worse."

Too many beetles

Surveys over eight nights in January 2024 secured around 200 beetles, which are now stored in the fridge in Dr Brookhouse’s lab at ANU, the same lab where he keeps Eve, the first beetle.

Almost all of them are Phoracantha mastersi, the species they’ve now proven to be responsible for the snow gum dieback.

But the dieback continues at an alarming rate. It has been identified by the NSW Government as one of the state’s most damaging ecological issues.

The same conditions that cause stress for the snow gums – drought and heat – are perfect for the beetles which are killing them, and climate change means those conditions are occurring with increasing frequency.

The loss of the snow gums would be catastrophic, and sadly there's nothing to be done to save the trees which are already damaged.

The only hope is to find a way to stop the beetles from spreading even further.

And now, finally, Dr Brookhouse has enough beetles, and enough data, to try.

His research focus is a possible sex pheromone produced by mating beetles, which he hopes could be used to lure and trap males in large numbers.

It was an idea which came to him while observing beetle behaviour in the field.

"That's the beauty of those endless nights," he says. "You just happen to make an observation – 'Gee, isn't that interesting? I wonder what's going on there?' – and then that becomes a key thing."

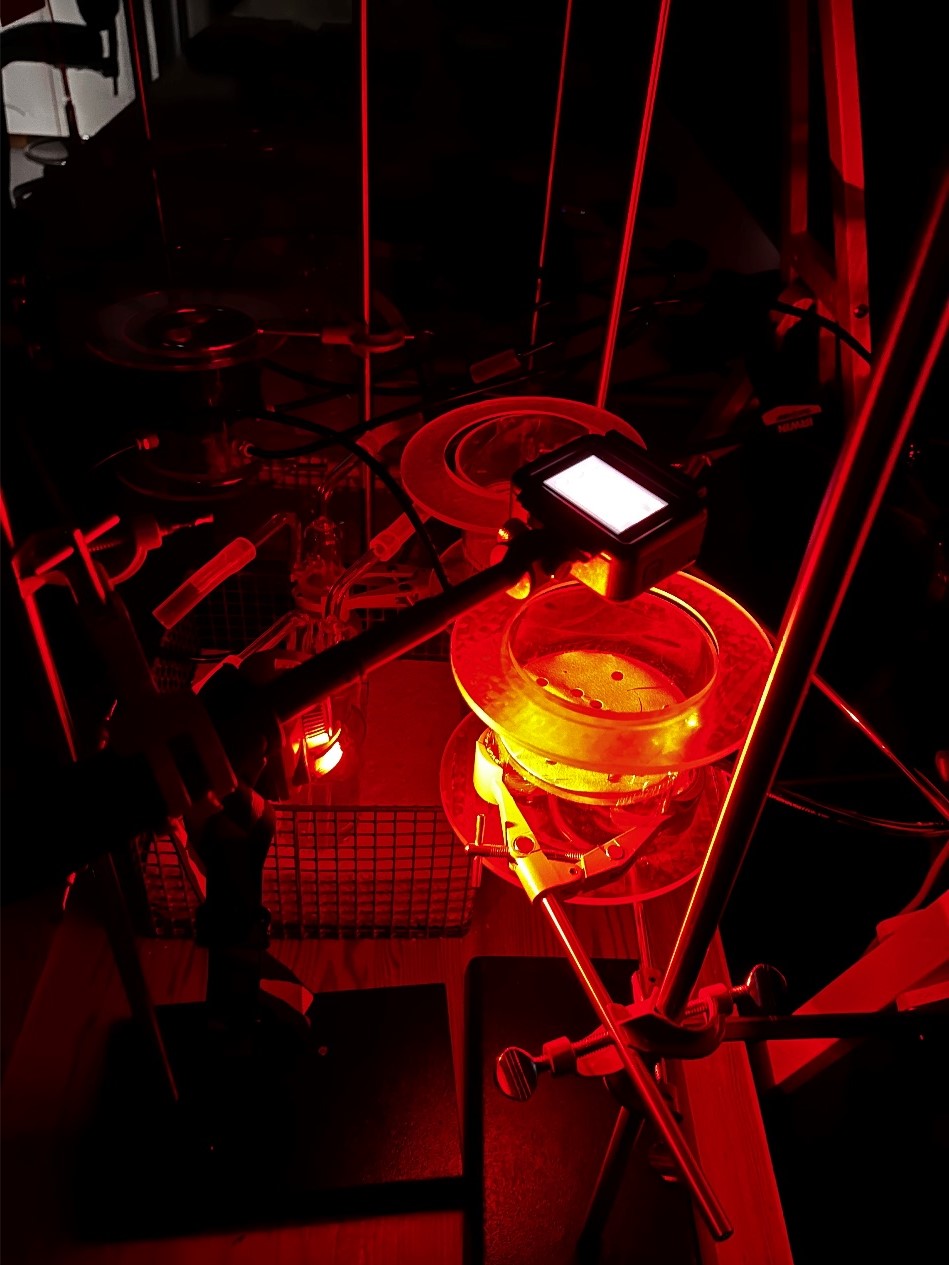

Soon he will black out the windows in his lab and use night-vision cameras to observe mating beetles in an olfactometer he’s rigged up.

He's excited, and hopeful.

"It’s a big problem, but we need a pathway to work towards a solution. Otherwise, where do we stand?"

Meyer now works as an entomologist in biosecurity and says those days and nights did nothing to turn them away from a career in ecology.

"No, it made me really excited about it! It was what I had hoped my science degree would be – I got to contribute."

It also, perhaps improbably, inspired a love of insects.

"I didn't know how much there was to be infatuated by," Meyer says.

"There’s an addictive quality to looking at this small thing and realising there's a huge, incredibly fragile, hyper-intricate system behind it and trying to figure out how it all works.

"There's a mystery to it, and that mystery became a foundational love for me."

It becomes personal, Dr Brookhouse agrees.

"The more something infuriates you, the more personal it becomes, and then, the harder it is to let it go.

"And it sure was infuriating."

Because everything is infuriating until it's a breakthrough.

Credits

Written by Tabitha Carvan

Animation, illustrations and design by Amanda Cox

Photography by Nic Vevers

Digital production by Ilario Priori