Wave physics encourages bacteria to grow biomaterials

Physicists at ANU have developed a way to use waves to manipulate the growth of bacteria biofilms – one of the most abundant forms of life on earth.

The team found the growth of biofilms in a liquid could be promoted or retarded by different regimes of wave motion set up in the liquid.

The breakthrough could help improve how we deal with chronic infections and antibiotic resistance, as well as the food we eat and the clothes we wear.

Lead researcher Dr Hua Xia said scientists have been trying to understand and control biofilms for decades.

“Formation of biofilm starts when the bacteria attach to the right type of surface. They’re formed by the bacteria to create a safe environment, to shield themselves from dangers,” Dr Xia said.

“For example, dental plaque is a common example of a biofilm. Outside our bodies, pond scum is another example. Biofilms thrive on moist or wet surfaces."

“But they’re not necessarily harmful to people. In wastewater treatment plants and agricultural technology, we utilise the ability of bacteria to form biofilms."

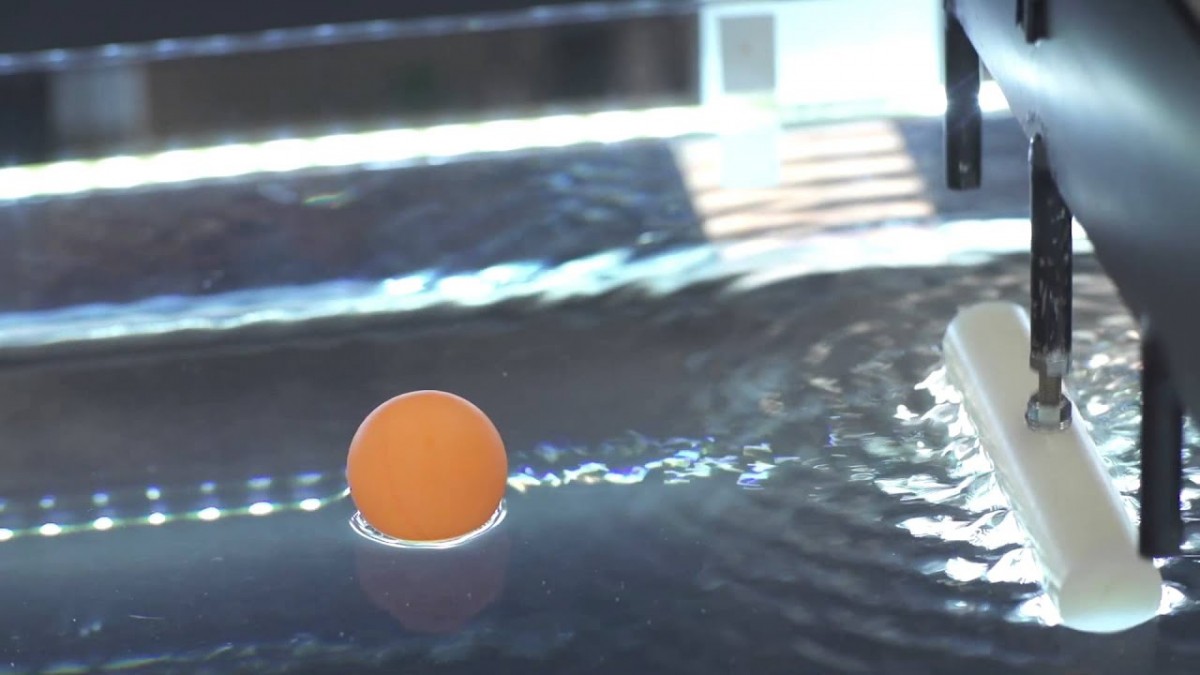

The team had previously shown that surface waves drive flow currents within a liquid. They used these findings to develop the new approach to controlling biofilm formation on the liquid-solid interface.

Using fluorescent dyes to visualise the currents, they found that turbulent motion discouraged the attachment of bacteria and biofilm formation. In contrast, stable flow regimes could encourage biofilms to grow into various patterns.

“We believe this is because stable flow patterns generate localised transport routes that connect the bottom of the container to the surface and deliver oxygen,” Dr Xia said.

The wave action is the strongest at the liquid-air interface, where some microorganisms form a compound called bacterial cellulose.

This wave-based approach could help engineer new forms of bacterial cellulose, which is used for everything from textiles and cosmetics to food products, as well as in the medical field for tissue engineering scaffolding, drug delivery and wound dressing.

“We’re now focused on creating various cellulose forms and controlling their properties, such as its water holding capacity or mechanical strength,” Dr Xia said.