The nuclear scientist planning life on other planets

By Amanda Diaz

What might life look like if humans were to move to another planet?

How could we have access to clean water, sustainable food sources and create a just society?

Lachlan McKie is part of a group of researchers considering the challenges of terraforming – or modifying the atmosphere, temperature and ecology of other planets to be habitable like Earth.

These experts, who come from disciplines including science, design, engineering and business, are gathered at the birthplace of the World Wide Web in Switzerland.

While their challenging task sounds like a storyline from a sci-fi movie, it’s part of a pilot program run by IdeaSquare at the European Centre for Nuclear Research (CERN), where the exercise is more about encouraging participants to consider how we can improve our own world.

“It’s a bunch of people who have very different perspectives on how the world works, and we’re trying to figure out what society could be if we didn’t have to operate in the framework we’re in now,” says McKie, who is a PhD candidate in nuclear physics at The Australian National University (ANU).

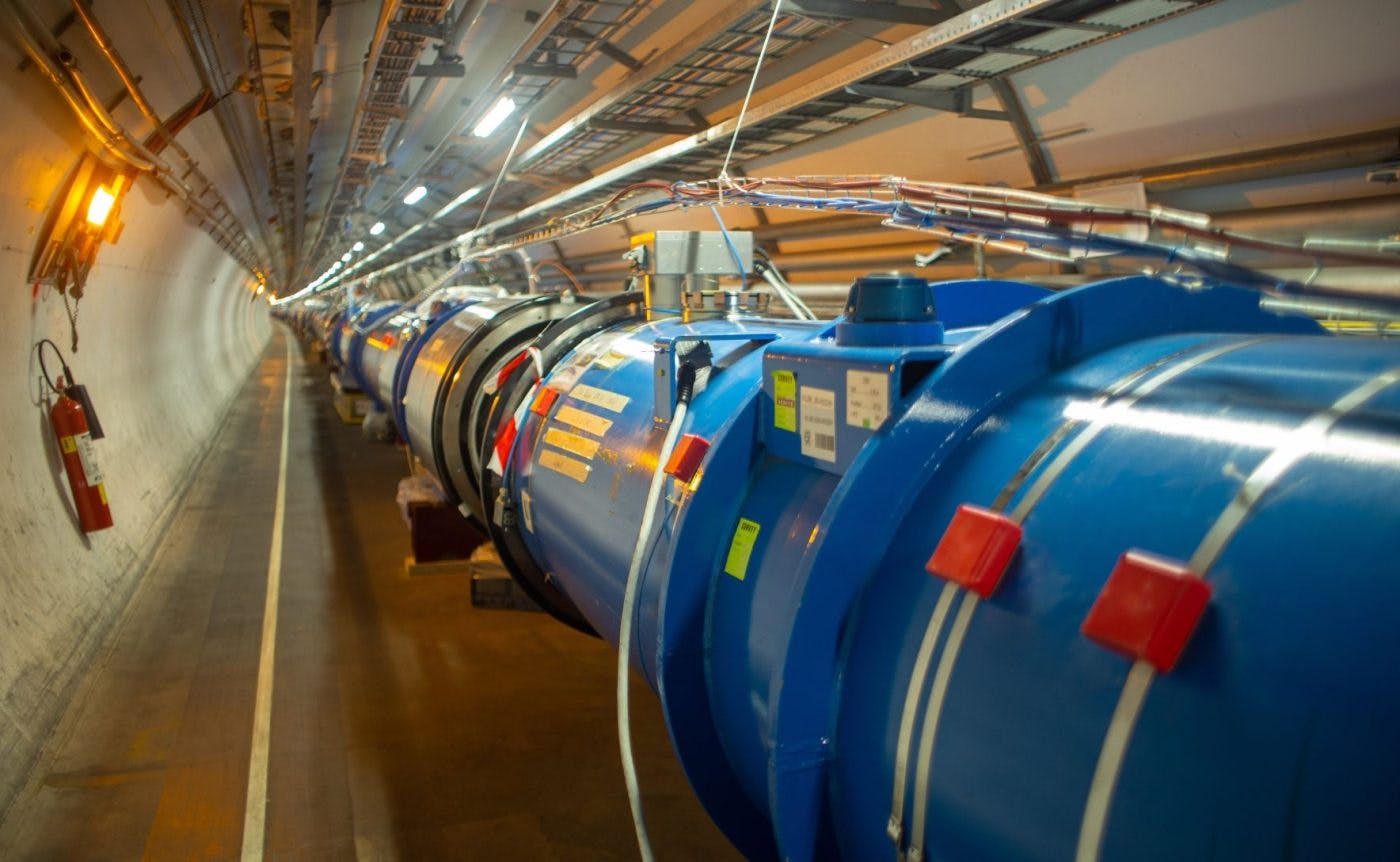

A glimpse inside CERN in Switzerland. Photo: francescodemarco/stock.adobe.com

Participating in Ideasquare is not McKie’s first time dealing in high-stakes hypotheticals. As part of his Master of Science (Advanced) in Nuclear Science at ANU, he explored the potential ramifications of Australia pursuing nuclear technologies including reactors and weapons.

“We had to look at how our Asia-Pacific neighbours would respond and whether it might be destabilising in the region,” he recalls. “It was quite a holistic education. I wasn’t just doing maths and science for three years, but also a lot of policy and international relations.”

Growing up in Orange in regional New South Wales, McKie always had an interest in science, but his mum and dad made sure he and his siblings were as well-rounded as possible.

“My parents always stoked our curiosity. You couldn’t spend all your time doing one activity,” he says.

“We did a lot of hiking, we did sports and Scouts, we had to have jobs. You weren’t just academic, you had to work in some aspect of society to make the overall system work.”

Although McKie originally started out studying mechanical engineering through the Australian Defence Force Academy, he switched to physics in his third year.

“I swapped to physics because I liked the more open-ended questions,” he says.

After leaving the army, McKie tried a few different jobs – including managing a science lab at a high school – but struggled to find his niche.

“In the back of my mind, I knew I had more to contribute and wanted to get back to learning more about that the world.”

His original plan was to study astrophysics, but an out-of-the-blue email from the nuclear science department at the ANU Research School of Physics changed his path.

“I walked in the doors one day, had a look around the labs and have never really left,” McKie says. “It’s been such an amazing experience; I’ve never even had to think about leaving.”

“It’s a very, very exciting time to be a nuclear physicist here.”

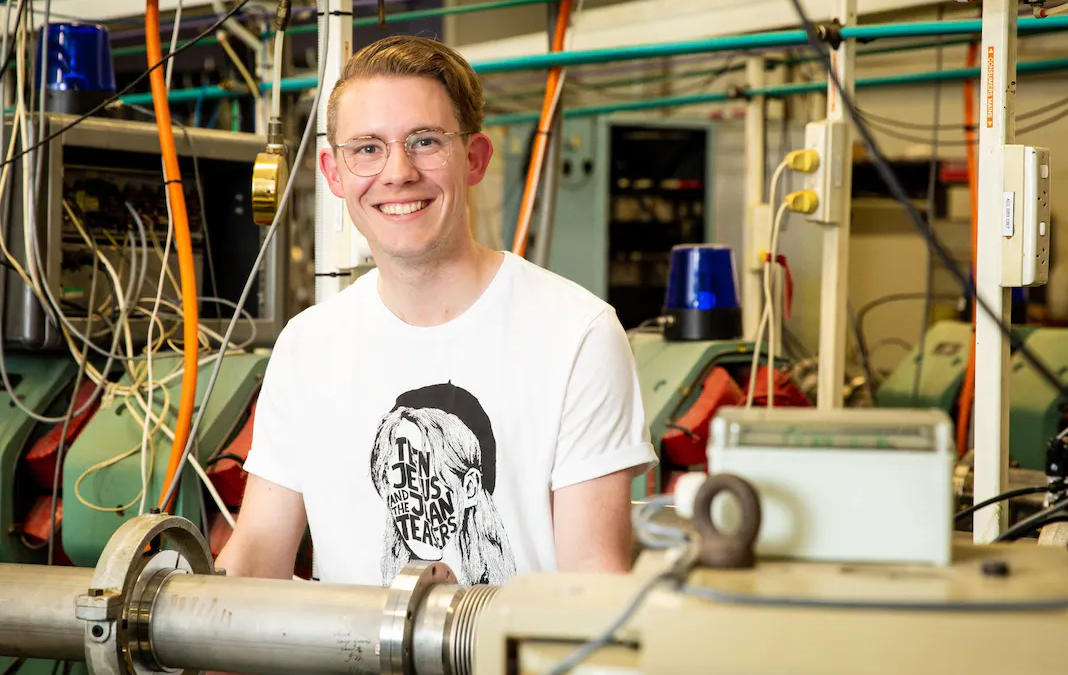

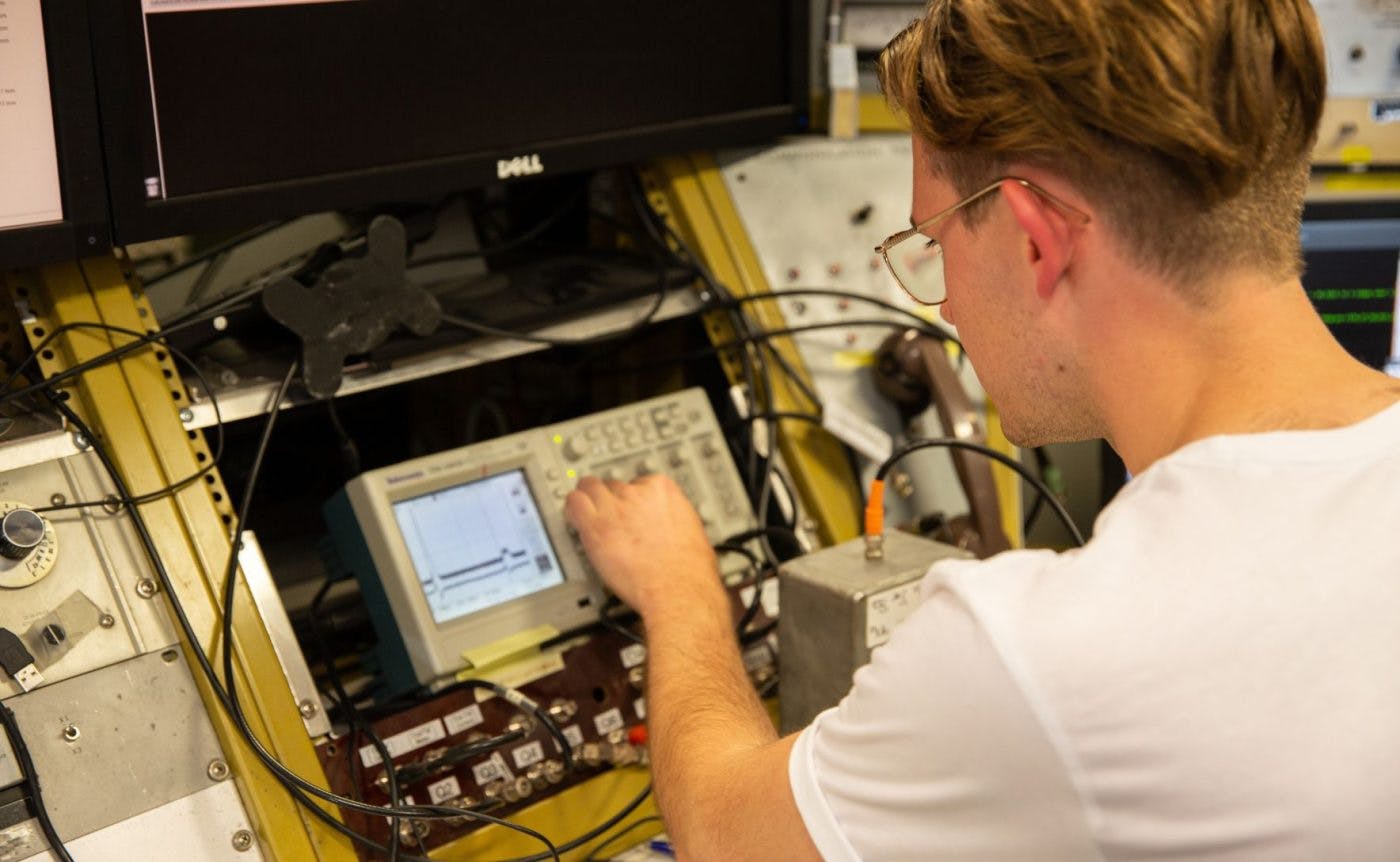

ANU PhD candidate Lachlan McKie

Having now spent time at CERN – “the holy grail of physics” – home of the Large Hadron Collider, and at the Heavy Ion Accelerator Facility on the ANU campus, McKie is in the privileged position of being able to compare the two particle accelerators.

“I don’t think that you can say one is objectively better than the other,” he says diplomatically. “At ANU, we do very different research, and I feel like we’re the only place in the world where you can do some of those things.”

McKie currently works as a member of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Dark Matter Particle Physics. As part of his doctorate, he is building radiation detection systems that may be able to assist in the search for dark matter, which scientists think could make up 85 per cent of our universe, while also having potential applications in other fields including medical imaging and environmental sciences.

The plan is to deploy the detectors in the Stawell Underground Physics Lab in Victoria.

ANU PhD candidate Lachlan McKie is building radiation detectors as part of his PhD. Photo: Martin Conway/ANU

“There are definitely ups and downs – experimental physics is difficult,” McKie says. “I’ve learned that the laws of physics don’t always hold when you’re building your own apparatus, but we do hope to have things up and running in the next year.”

While McKie would like to complete a postdoctoral fellowship overseas, his goal is to return to Australia afterwards.

“It seems like our nuclear industry is at a turning point, with the building of the submarines,” he says. “It’s a very, very exciting time to be a nuclear physicist here, and I hope to be a part of it.”

From studying life beyond the stars to unravelling the mystery of how life on Earth became possible, a day in the life of a nuclear scientist is anything but ordinary. If this sounds like the career for you, check out the Bachelor of Science and Master of Science in Nuclear Science degrees on offer at ANU.

You can learn about other fascinating nuclear science discoveries from ANU at the Research School of Physics website.

This article first appeared on ANU Reporter.