Big dreams of very tiny things

As a young girl in Bangladesh, Victoria Uttaree Bashu was obsessed with Einstein.

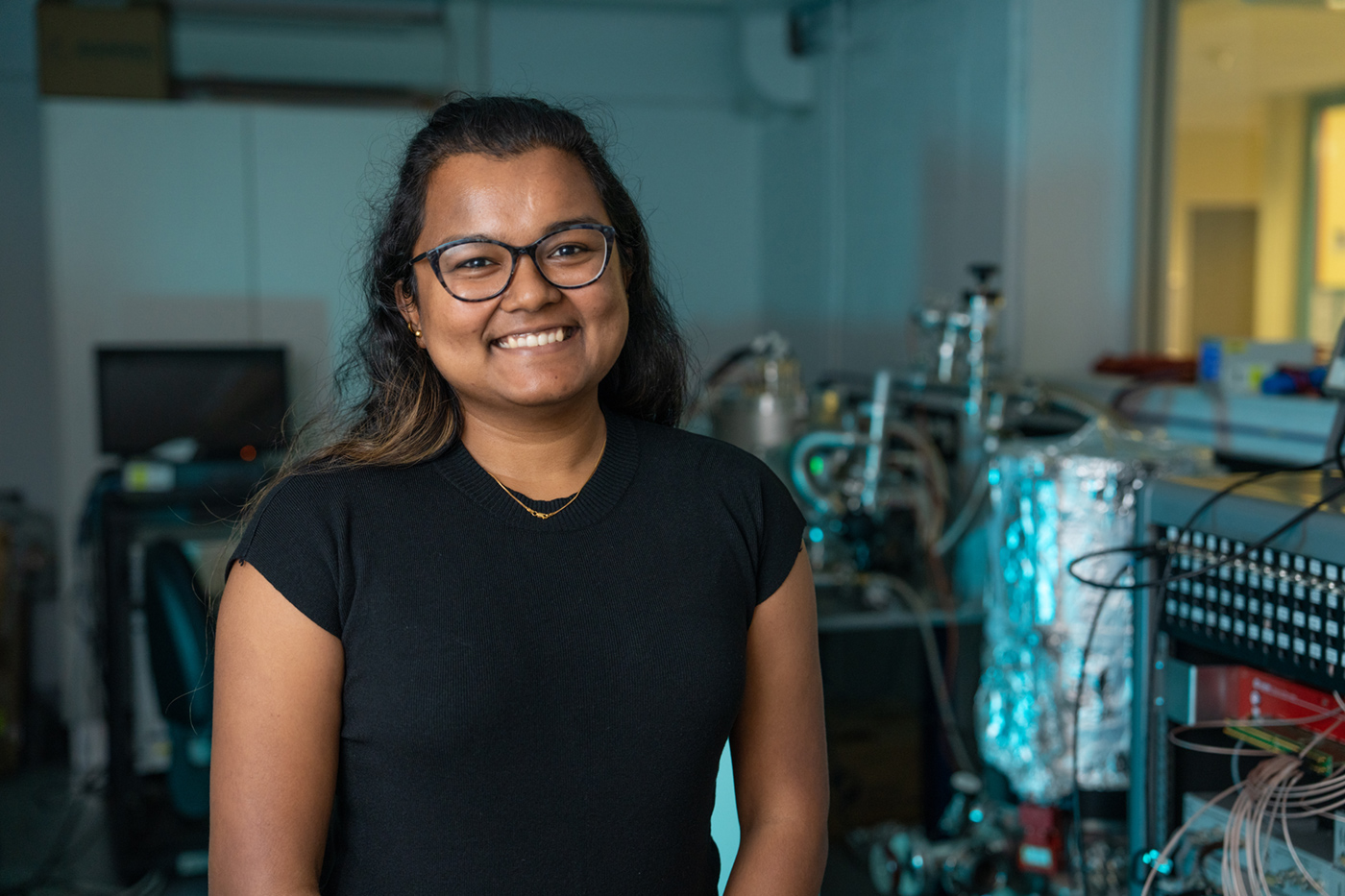

Like her inspiration, she is already pushing back the frontiers of physics, three months into her PhD in the Nuclear Physics and Accelerator Applications Department.

“Sometimes I see something on screen, and it is the first time anyone has noticed that. Even if it is a very tiny thing in the whole field, still it is exciting to be doing something of my own.”

Very tiny things are exactly what Ms Bashu is looking for. She’s part of the global team building the CYGNUS (CosmoloGY with NUclear recoilS) detectors, which will search for dark matter – thought to be very small particles surrounding us, that interact with normal matter on only the rarest occasion.

Hopefully CYGNUS will catch those rare occasions, unveiling tracks of dark matter particles through its low-pressure gas chambers. The clincher will be if the scientists can distinguish the dark matter wind caused by the earth’s movement through space – the solar system is moving towards the constellation Cygnus – and can separate out the similar tracks caused by neutrinos, which mostly originate from the sun.

The search for dark matter seems an impossible challenge, but that’s nothing new to Ms Bashu; becoming a physicist seemed an impossible dream for her.

“At high school back home I always wanted to study physics, but I felt I was the only one with that idea,” she says.

“If you do well as a girl you’re expected to do medicine, and boys do engineering.”

Fortunately her parents supported her to follow her dream to study physics in Australia, doing her undergraduate degree at Macquarie University. A drawcard was to be near her sister, who was also living in Sydney.

“It was nice to have someone in this foreign country – I had never lived without my parents before,” Ms Bashu says.

The personal touch was important for her choosing ANU – when she reached out to Dr Lindsey Bignell to apply, he organised a tour of the Heavy Ion Accelerator for her.

“It’s a lovely team; people are welcoming, and it’s one of the most balanced in gender ratio.”

“There is cultural diversity too – it helps, I don’t feel odd,” she says.

“Diversity is good for the science too, we need to be open-minded to everyone’s perspectives.”

The language was a challenge at first for the native Bangla speaker.

“We have English as a high-school subject, but the Australian accent… that was a cultural shock!”

She’s conquered the language and now regularly tutors undergraduate physics and maths – something that she’s determined to make part of her career.

“I love teaching. If only one student says ‘that makes so much more sense now!’ then that makes it all worth it,” she says.

Just months into her PhD Ms Bashu has become the face of team, with pictures of her inside the tank of the 15 million volt accelerator splashed across major media publications as part of an ANU ad campaign for nuclear science courses – simply because she was in the right place at the right time.

“It was a coincidence – the day the photographers were there, only Lindsey and I had the training required to go inside the tank – hence being the face of ANU and Nuclear Physics!”

You get the sense that if anyone is going to be in the right place at the right time when the elusive dark matter particles show up, it will be Victoria Uttaree Bashu.

This article was first published by ANU Research School of Physics.